24. Backbox Hardware Installation

This section continues with the cabinet trim hardware, moving on now to

the backbox.

We assume that you've already built the wood shell of the backbox as

described in Cabinet Body, and that you've already painted it

and/or applied decals, as described in Cabinet Art. It's best

to finish the artwork before installing any hardware, since some the

hardware will get in the way of painting or applying decals once

installed.

As with the Cabinet Hardware Installation chapter, we try to present things

in an order you can follow for installation.

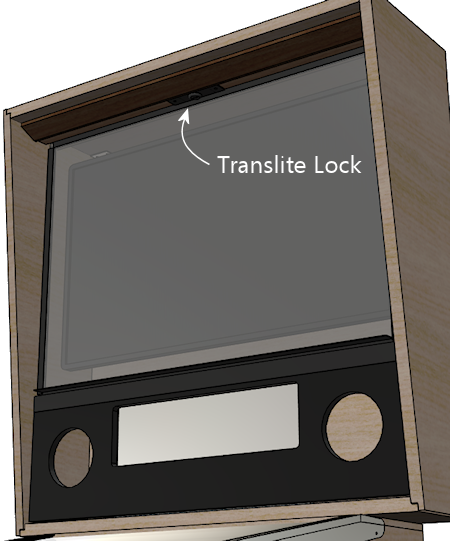

Translite lock

The real machines have a keyed lock at the top of the backbox that

secures the translite, so that arcade customers can't steal the

translite or get into the backbox to mess with the electronics.

The operating principle is pretty simple. In the locked position, a

metal tab on the lock sticks into the slot at the top of the backbox

trim that the translite fits into. This prevents lifting the

translite, which is necessary to remove it.

In the unlocked position, the metal tab swings out of the way, letting

you lift the translite into the slot, which in turn lets you remove it.

With the lock open, there's enough play that you can remove the

translite, as described below.

With the lock closed, the tab prevents moving the translite far enough

to free it from the top and bottom trim channels, so it's effectively

locked in place.

The translite lock is purely for the sake of security - it's there to

prevent anyone without the key from removing the glass. The glass

won't fall out on its own, though, even if you don't install the lock

- it's held in place by the slots it sits in, and you have to

intentionally maneuver it out of the slots to remove it. So it's not

a functional necessity in a home setting, unless you have obnoxious

friends. (The exception is that the glass could conceivably come

loose during transport if you give it a bumpy enough ride. A lock

does help prevent this by ensuring that the glass can't move out of

its slots.)

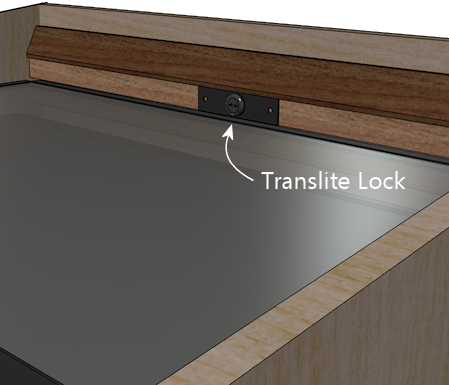

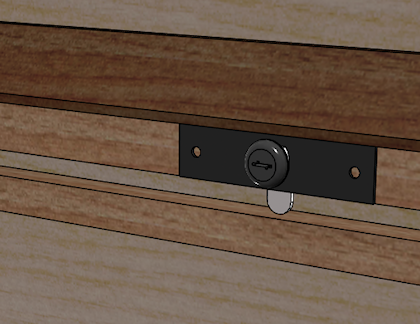

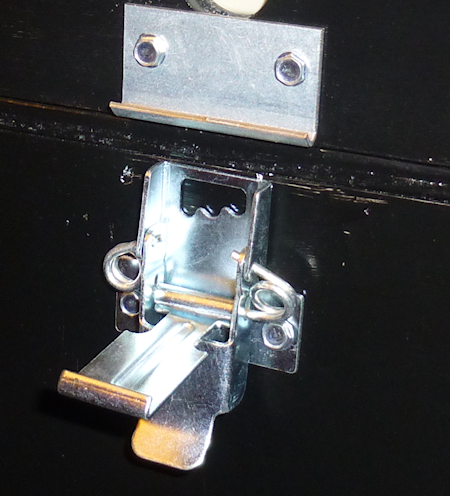

Installing the translite lock

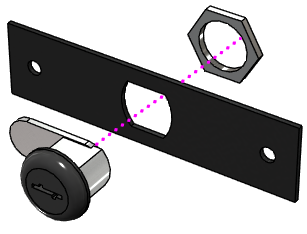

First, assemble the pieces of the lock plate. Slip the lock through

the hole in the plate, slip the hex nut over the back of the lock,

and tighten the nut.

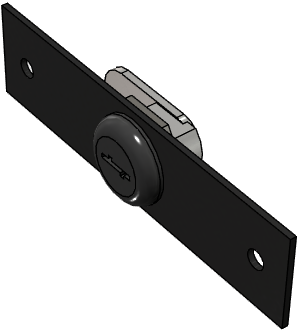

It should look like this when assembled.

The pinball vendors sell the lock plate assembly as a complete kit,

which includes a pair #8-32 machine screws with security Torx heads.

There are two reasons you might want to discard these and substitute

your own wood screws. The first is that they're the security Torx

type, so you need the special security type of Torx driver to use

them. "Security screwdriver" is a bit hyperbolic when anyone can go

buy one at Home Depot, but it's at least a slight deterrent against

mischief simply because most people don't have one lying around. The

second reason you might be inclined to discard the special screws is

that they're machine screws, not wood screws. They won't attach well

to plain wood. They require T-nuts, which must be pre-installed

behind the trim, as explained in "Translite lock plate preparation" in

Cabinet Body. If you skipped that step

when installing the trim, it's probably too late. Fortunately, wood

screws are a pretty decent alternative, especially if you're not

concerned about the security aspect of the lock. And if you are

concerned about that, you could substitute tamper-resistant wood

screws.

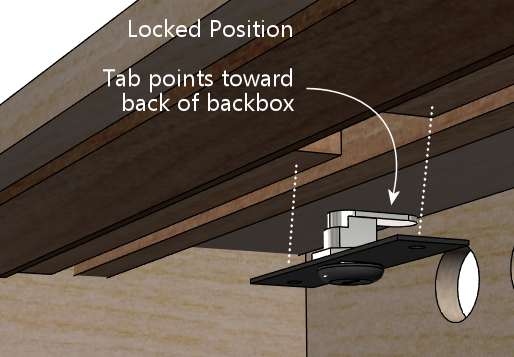

Before installing the lock plate, use a key to check the orientation

of the lock. Turn the lock so that it's in the extended position,

with the lock tab sticking up perpendicular to the plate. Be

sure to install it with the tab facing the back of the backbox.

If you did already install T-nuts for the Torx screws, simply put the

lock plate in position, and fasten it with the Torx screws.

If you didn't install the T-nuts, discard the Torx screws that came

with the kit, and substitute a pair of wood screws. I'd go with #6 x

¾". Rounded-head screws will look better, as will black screws

if you can find them (if not, you can just paint the heads black after

installation if you want).

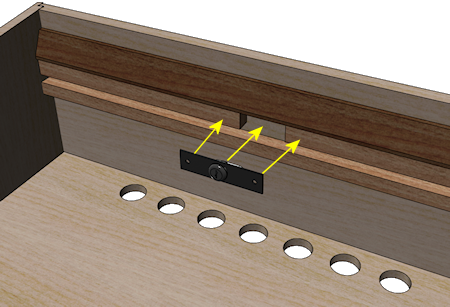

Line up the lock plate over the gap in the top trim. It should be

centered over the gap, which should be the same as centering it

side-to-side overall in the backbox. Mark the positions of the screw

holes. Remove the plate and drill pilot holes for the #6 screws. Put

the lock plate in position again and fasten the screws.

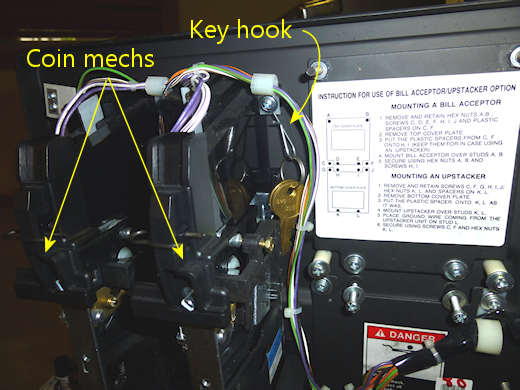

Where to keep the keys

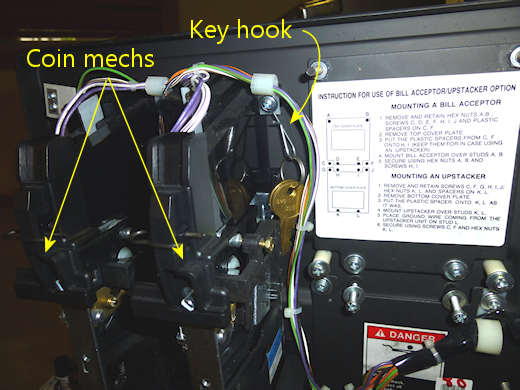

With the real machines, the standard way to keep track of your

translite keys is to keep them on a little hook inside the coin door.

The WPC and SuzoHapp doors provide a hook specifically for this

purpose, located next to the coin mechs.

If you're not installing a standard coin door or can't find the key

hook, you might put a little eyelet or hook on the inside wall of the

cab somewhere convenient, and hang the keys there.

DIY alternatives

If you don't need the locking function, but your backbox has the gap

in the trim where the lock plate goes, I'd simply install a 1" x 4"

plate, either metal or a thin piece of wood, painted black. Screw it

in with #6 x ¾" wood screws, at holes placed about ⅜"

from either edge. Use rounded-head screws, and either use black

screws or paint the heads black after installation.

If you haven't yet installed the wood trim where the plate goes,

I'd simply run a single piece of wood all the way across rather

than replicating the gap in the standard plans.

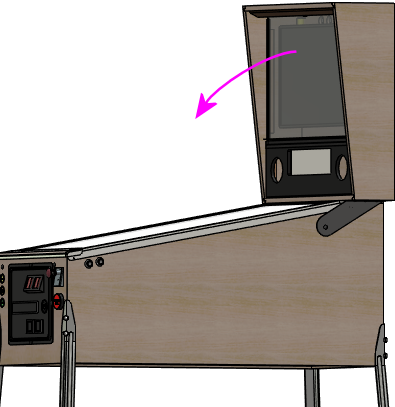

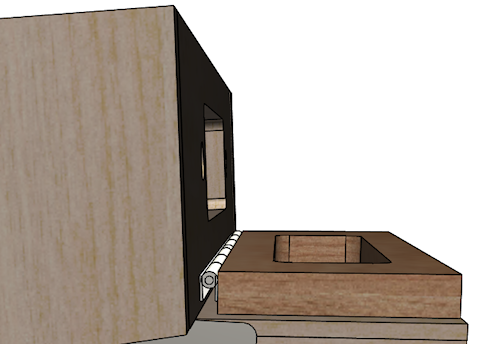

Backbox hinges

Real pinball machines are designed with a hinge that lets you tilt the

backbox forward until it's lying flat on top of the main cabinet.

This is an essential feature if you want to transport a pinball

machine, as it would be too tall, top-heavy, and fragile with the

backbox in the normal position. And you certainly wouldn't want to

remove the backbox every time you moved the machine, as that's a major

operation that requires disconnecting a lot of wiring, which always

creates a risk of breaking something when you reassemble it.

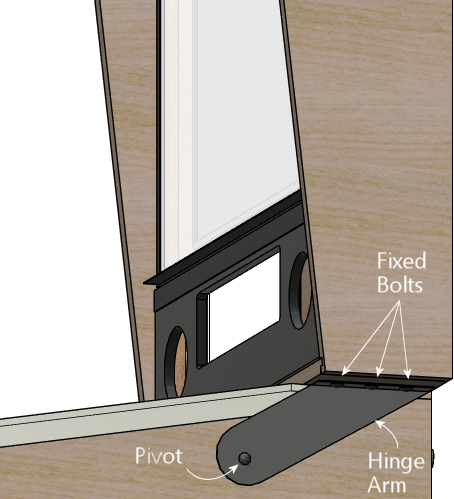

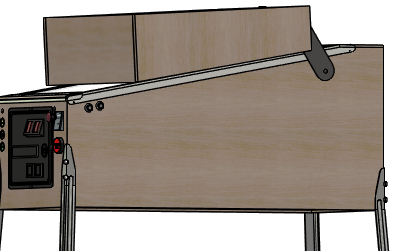

WPC hinges

On the WPC machines, the backbox is attached to the main cabinet with

a clever hinge mechanism that uses rotating arms connected to pivots

on the sides of the cabinet.

I consider this setup clever, in part because it wouldn't have

occurred to me to do it this way, but mostly because it has has some

nice functional advantages over the more obvious "door-hinge"

approach, where you simply put a regular hinge at the front of the

backbox. A door-hinge approach is workable, and in fact it's used

on a lot of older pinball machines from before the WPC era - we'll

have more on this shortly, since it's a viable alternative if the

WPC approach doesn't work for you for some reason. But the WPC

system more elegant: it looks nicer, it makes for simpler cabinet

geometry, and it's easier to install and to get everything aligned

properly. Door-hinge systems can be tricky to get aligned.

So assuming you're building a full-scale cabinet, the WPC approach is

all upside. And it's not particularly expensive; the required parts

will only set you back about $30.

The only reasons I can think of not to use the WPC hinges are (a) that

you're building a mini-cabinet that's too small for the standard parts

to fit properly, or (b) that you're specifically reproducing a cabinet

style from a different era, so you want to use the same hinge system

they used. If one of these applies to your build, you can skip down

to the "Alternatives" section below for some other ideas.

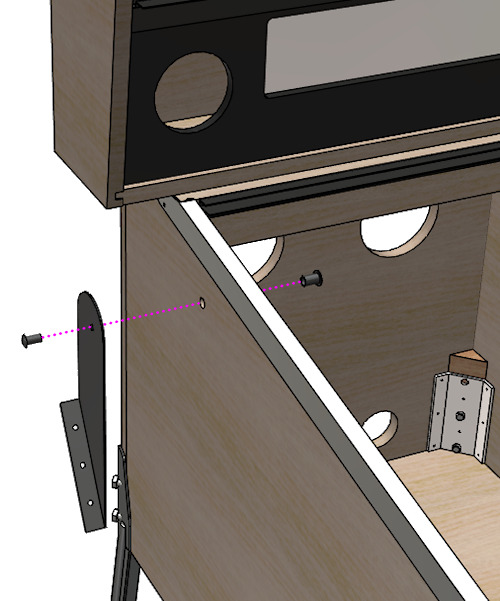

Installing the WPC hinges

One of the advantages of the WPC hinge mechanism is that it's

easy to set up. If you followed the WPC cabinet plans in

Cabinet Body, you've already drilled the mounting holes in

the main cabinet and backbox. To review, the parts get mounted

here:

...and here:

See "Backbox floor" in Cabinet Body for

drilling locations, which depend on your cabinet width. If you

haven't already drilled these, an easy way to figure the exact

position is to use the hinge arm itself as a drilling template, after

attaching it to the main cabinet first. We'll point out the right

time to do that in a moment.

You should already have your side rails installed at this point, since

the hinges will get in the way of installing them later.

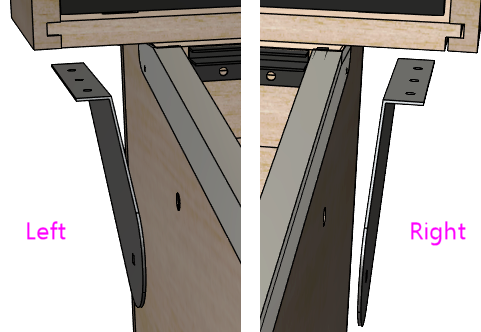

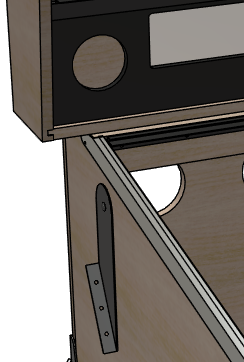

Note that there's a "left" and a "right" hinge arm - they're mirror

images. Be sure to install the correct one on each side. They should

be oriented with the pivot point pointing towards the front of the

cabinet, and the little "wing" that attaches to the backbox pointing

away from the cabinet side:

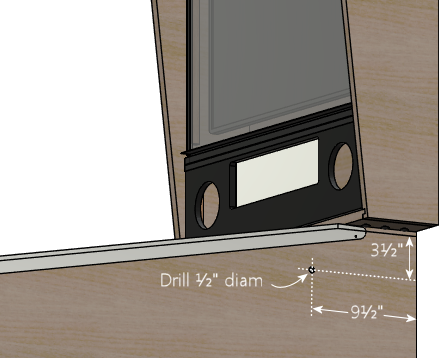

Start with the hinge pivot joint. This uses the ½" diameter

hole drilled in the side of the main cabinet:

- Fit a ⅜"-16 x ¾" carriage bolt into the squarish opening on the side of the hinge arm. Orient the hinge arm so that it's hanging from the bolt, so that it doesn't swing down into this position on its own and scratch the side of the cab.

- Insert the carriage bolt into the pivot hole in the main cabinet

- From the inside of the cabinet, thread the pivot bushing (Williams part 02-4352) by hand onto the end of the carriage bolt

- Use a ¼" hex wrench to tighten the pivot bushing from the inside of the cab

When tightened, this arrangement should leave a little clearance

(about 1/8") between the hinge arm and the main cabinet, and you

should be able to rotate the hinge arm around the pivot. (It's okay

if it's tight.)

Install both hinge arms (left and right) using the procedure above.

Position the backbox on the shelf at the back of the cabinet, centered

side to side, with its back flush with the back wall of the main

cabinet. (Have an assistant hold the backbox steady while you're

working so that you don't accidentally knock it over.)

Rotate the hinge arm around the pivot until the side with the three

bolt holes meets the bottom side of the backbox. Be careful about

rubbing the sides of the cab so that you don't scratch the artwork.

If you haven't already drilled the holes in the backbox floor for

attaching the hinge bracket bolts, this is the time! Make sure the

hinge arm is flat against the bottom of the backbox, and that it's

precisely parallel to the side of the cab. You should be able to see

a little gap between the hinge arm and cab across its whole length.

The hinge shouldn't be pressing against the cab anywhere, since that

could scratch the artwork when you rotate the backbox. Once you have

it aligned to your satisfaction, mark the positions of the three bolt

holes. Repeat on the other side. Remove the backbox and drill

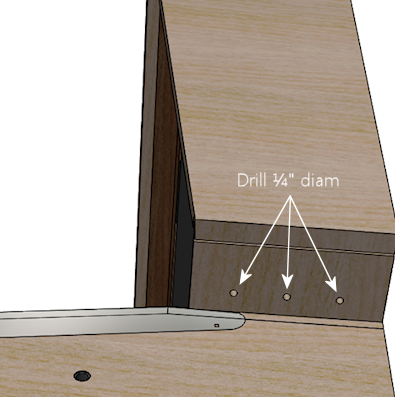

¼" holes at the marked positions.

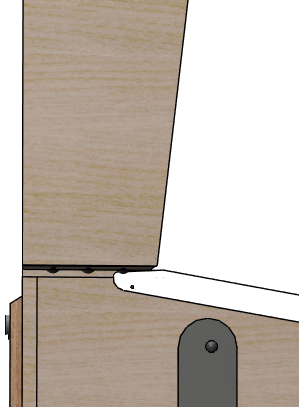

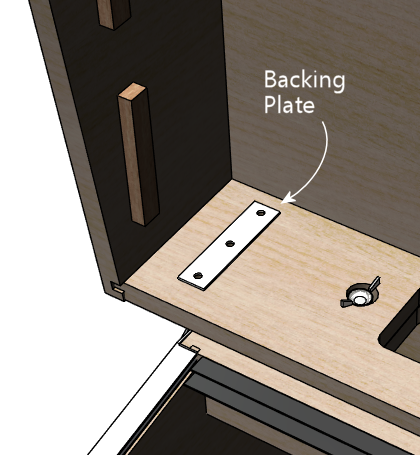

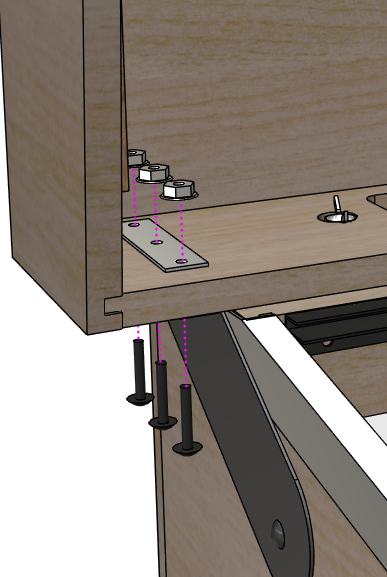

On the inside of the backbox, position the backing plate

(01-9012) over the bolt holes.

Install three ¼"-20 x 1¼" carriage bolts in each hinge

arm, inserting from the bottom side, and through the mounting plate.

Fasten each with a ¼"-20 whiz flange locknut. Tighten

securely.

The backbox is now attached! You should be able to freely tilt it

forward so that it lies flat against the top of the cab. (It's a good

idea to put down some padding when doing this, so that you don't

scratch up the side rails or the front edges of the backbox.)

If you ever need to remove the backbox, just take out the carriage

bolts attaching the hinge arms to the bottom of the backbox. You can

leave the hinge arms themselves attached permanently.

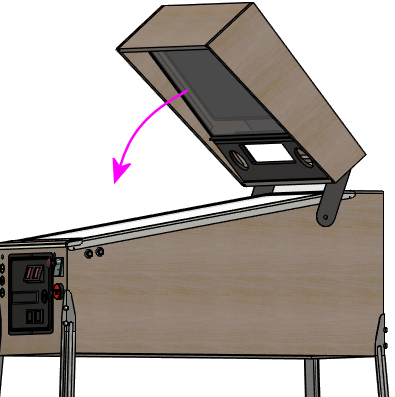

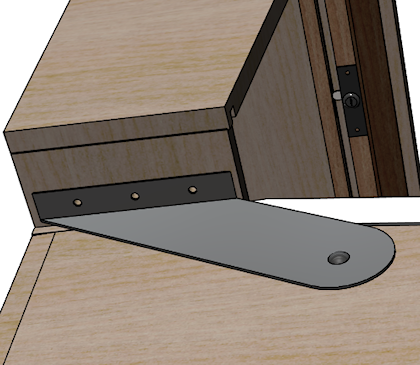

Alternative hinge mechanisms

Most commercial machines made from the 1990s to present use the WPC

hinge system described above. Most earlier machines that I've

encountered use something more like conventional door hinges, with the

hinges attached at the bottom front of the backbox. The backbox folds

down forwards onto the cabinet, as in the WPC system, but the pivot

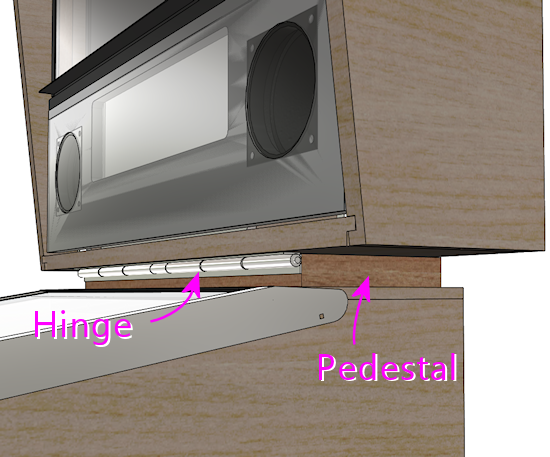

point is the door hinge rather than the side bolts. The Williams

System 11 machines from the 1980s use this approach, as shown below.

Williams System 11 backbox mounting (Space Station,

1987). This used door hinges at the front of the backbox.

Note how the backbox has to be raised slightly above the

cabinet on a pedestal, to make space when folded down

for the part of the backbox that overhangs the front of the hinge.

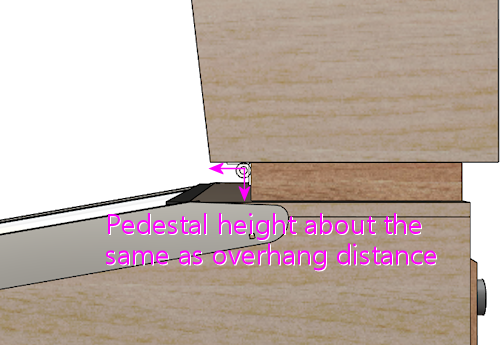

I think the WPC system is nicer in a lot of ways, but the door-hinge

system might be a good alternative in cases when the WPC parts won't

fit, such as a mini-cab or an ultra-wide cab. If you use the System

11 machines as your model, pay close attention to the way it requires

a "pedestal" to raise the backbox about an inch above the main

cabinet, to make room for the front overhanging portion of the backbox

when it folds down. The standard WPC plans won't work well with a

hinge like this, because the backbox sits directly on top of the

cabinet in the WPC design. If you want to adapt the WPC plans for

this arrangement, you'll have to add something like the System 11

pedestal.

The pedestal has to be at least as high as the distance

the backbox projects out in front of the hinge, to make

room for that part when the backbox is folded down.

Hinge system with backbox folded down.

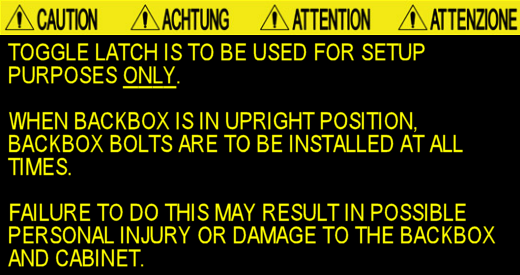

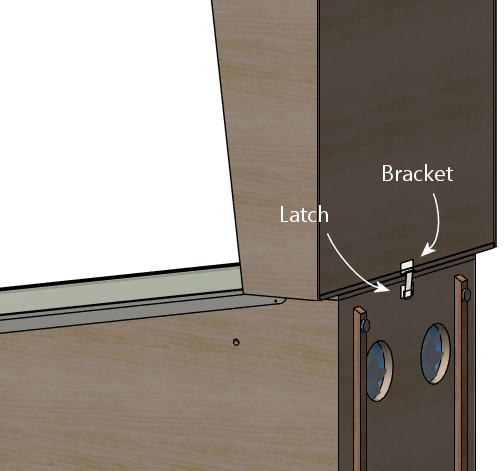

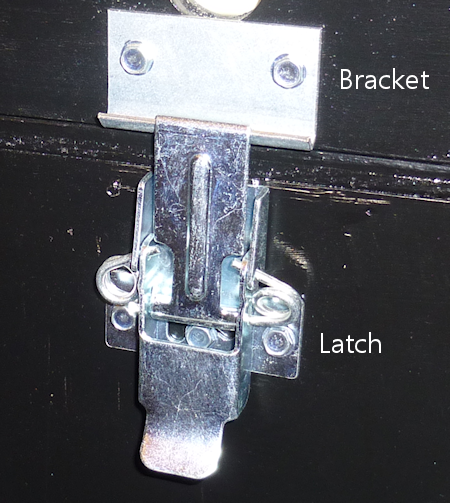

Backbox latch

This is a minor bit of hardware that helps when setting up the

machine, by temporarily securing the backbox in the upright position,

preventing it from falling forward if bumped. The standard part is a

simple toggle latch that attaches to the back of the main cabinet, with

a mating bracket that attaches to the back of the backbox.

I said "temporarily", because the toggle latch isn't strong

enough to serve as a permanent way of securing the backbox. Let me

show you the warning that they silkscreen on the back of the real

backboxes in big yellow letters:

Their point is that this little toggle latch isn't all that strong; it

could fail if the backbox were bumped too hard. The backbox is quite

heavy and has a lot of leverage, so you need something a lot stronger

to truly secure it. The solution is to install the wing bolts

described below. The toggle latch is just meant to be a temporary

helper while you're getting the wing bolts in place.

Install this after you've set up the backbox hinges, so that you're

working in terms of the actual final alignments.

For fasteners, use any suitable wood screw. On the real machines,

they usually use #6 x ¾" sheet metal screws with hex heads. (I

know, "sheet metal screw" doesn't sound like the right thing for

screwing into wood, but they actually work just fine as self-tapping

screws with plywood.)

- Set up the machine with the backbox in the upright position. Have an assistant brace the backbox while you're working so that it doesn't fall forward.

- Attach the bracket (the top piece) first. Align it in the center of the backbox side-to-side, with the bottom edge roughly flush with the bottom of the backbox.

- Figure the position of the latch itself by hanging it from the bracket with the lever pulled partially open, so that there's no tension on the spring, as illustrated below.

- Fasten the bottom bracket at this position. When you close the latch all the way, it should pull the spring tight so that the bracket stays latched.

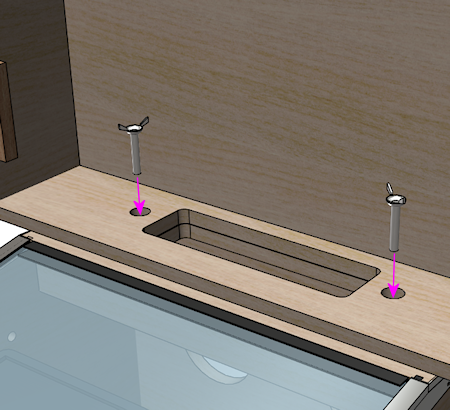

Backbox safety bolts

As the warning placard above points out, the little toggle latch on

the back of the backbox is helpful to keep the backbox from flopping

over while you're setting up the machine, but it's not strong enough

to rely on beyond that. For a deployed machine, you need something

stronger, specifically a couple of big bolts installed in the floor of

the backbox.

The parts required are a pair of ⅜"-16 x 2" "wing bolts", like

the one pictured below. Wing bolts are basically just regular bolts

with wing nuts in place of the heads. This lets you turn them by

hand, for tool-free installation. (The wing nut at the top isn't a

separate part; it's integral, like the hex head on a regular bolt.)

The wing nut head also serves as a built-in washer.

You can buy wing bolts in the right size from pinball vendors. You

might be able to find them at some hardware stores as well, although

they're too obscure for the big-box stores like Home Depot. In a

pinch, you could substitute ordinary hex-head bolts of the same size,

but note that you'd need to use some kind of giant washers (over 1"

outside diameter) in conjunction, because the hex heads by themselves

will slip right through the 1" top holes (defeating the purpose).

If you've done the necessary prep work as described in the "Rear

shelf" section in Cabinet Body, installing the bolts

is trivial. Just pass them through the holes on either side of the

floor opening and thread them into the pre-installed T-nuts. There's

no need for washers or other parts. Hand-tighten. You don't have to

go beyond hand-tight, since they don't have to hold the backbox up

most of the time; gravity takes care of that for the most part.

The bolts only kick in if the backbox gets bumped or pushed.

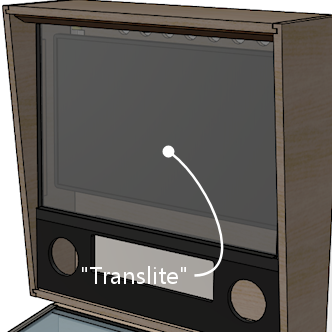

What is a translite?

We're all pinball nerds here, so a quick digression on definitions is

in order! There's a bit of a disagreement between virtual

pinball people and real pinball people about what "translite" means.

So to avoid confusion, I want to make sure we're all clear on what

we mean by the word.

Throughout this guide, I use the term "translite" to refer to a

clear plastic or glass sheet that you install in front of the main

backbox TV. There's no artwork printed on it (other than perhaps

some masking around the edges, to hide the TV bezel), since we want to

let the TV handle all of the artwork display. The virtual translite

is thus essentially a bit of trim in a virtual cab to disguise the

TV-ness of our virtual setup and make it look on the outside more like

a real pinball machine.

Okay, so that's how I use the term in this guide. It's also how

the term is commonly understood in the virtual pin cab community, so

that's the way you'll usually see it used on the forums. But

technically speaking, it's wrong! At least, it's not what it means

to (most) pinball people when they're talking about the real machines.

Technically, in a real pinball context:

- A translite is a thin, translucent plastic decal, printed with graphics. There's no glass involved in the translite itself. This plastic decal that they call the translite is then affixed to a clear glass sheet to create a pseudo-backglass. Most modern pinball machines (1990s and later) use this type of assembly in place of a true backglass. It's only a "pseudo" backglass because...

- A backglass is a glass sheet with artwork directly painted or silkscreened on the glass. True backglasses were usually used on machines built before about 1990, when the manufacturers switched to the cheaper translite process.

Those are the technical meanings, but even real pinball people often

use the words translite and backglass loosely and

interchangeably. They'll often call the translite-plus-glass assembly

a translite, or even a backglass. So I think we virtual pinball

people can be forgiven for appropriating translite to mean

kind of the opposite of what it really means, in that we use it to

refer to the plain glass sheet without any artwork.

Creating a translite

The basic material for the translite is a clear sheet of either glass

or acrylic. If you're using glass, it should be tempered glass. I

personally prefer acrylic for the translite because it's so much

lighter than glass.

Dimensions for the standard WPC-style translite:

- Thickness: ⅛"

- Size: 18⅞" high x 27" wide

The size obviously depends on your backbox dimensions.

The size above is for the standard WPC setup, with the backbox built

to the standard dimensions and a standard-sized speaker/DMD panel

installed. If you're not using a speaker panel, you'll probably want

to increase the height to cover the entire backbox area, so you'd make

it about 26½" high if you're using the standard backbox

dimensions.

Where to buy: The clear glass or plastic sheet isn't something you

can find as a standard pinball part from any vendor. Fortunately, it's

easily found as a generic part.

- For glass, you can have a custom glass sheet made by just about any window glass company. Look for local companies that install or repair residential window glass.

- For acrylic, try TAP Plastics or a similar local plastics vendor. You can also buy acrylic in standard sizes at Home Depot and other hardware stores, and cut it to a custom size yourself using a plastic knife. This doesn't tend to make as clean an edge as you'd get from a plastics shop, but that doesn't really matter, since the edges are all covered by trim pieces anyway.

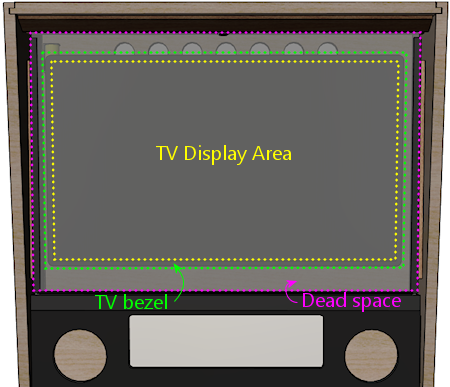

Edge masking

It's nearly impossible to make the backglass TV fill the entire space

that's available for the translite in the standard backbox design.

Part of the reason is that a TV's viewable screen area never

completely spans the full height and breadth of the unit; there's

always at least a thin bezel around the edges. The other factor is

that the backbox space is much squarer than the 16:9 aspect ratio

that's all but universal on current TVs. It's impossible to find a TV

that fills the vertical space fully, given the constraint of also

fitting in the available width. You can get down to a fraction of an

inch of dead space on the sides, but you'll still have more than an

inch at the top and bottom in the best case.

Most cab builders want to cover up all of the dead space around the

edges of the TV, so that only the live display area of the TV is

visible. Understandably, they don't want the insides of the backbox

to be visible.

One way that some cab builders deal with this is to create a wood

(or similar) cover with a cutout for the TV area.

I don't personally like this look very much, because to my eye, it

calls attention what it's meant to hide. I mean that it makes it more

even more obvious than it otherwise would be that there's a smaller TV

embedded in a bigger backbox space. I also find that it looks too

different from the real machines, which creates an impression of

home-brew-ness that's at odds with my goal of a realistic appearance.

Given that we're talking about translites, I think you can probably

guess that the approach I prefer is to use a clear glass or plastic

cover for the whole area. That's exactly what the real machines use,

so it looks as close to authentic as you can get, given the inherent

differences in what's behind the glass. But that still leaves the

problem that you can see into the dead space around the TV, since

a clear glass or plastic cover is, after all, clear.

The best solution, in my opinion, is to combine the "cutout" idea from

the wood cover with the clear translite, by masking out the edges of

the translite. There are two ways to do this:

- The easy way is to paint around the perimeter with black spray paint. Paint on the back side of the panel, so that the front has a uniform glossy sheen - that'll largely eliminate the visibility of the "cutout" that I find objectionable in the wood cover approach. Measure the TV display area size, and use masking tape and paper to cover the cutout area. Paint around the edges.

- The other way is to use printed decals to create the mask. You can have custom decals made for this use just like for the cabinet artwork (see Cabinet Art). I used this approach for my own cab, because I figured the real machines have artwork here, so I should too.

I used decals printed in the conventional way, to adhere to the front

side of the translite. It would have been better to print them in a

reverse format, with the adhesive on the graphics side so that they

could have been stuck to the back side of the translite. This would

have created a more uniform finish on the front, just like why you

want to paint on the back if you're using a painted mask.

I really like the way my translite with decals turned out, but for

practical purposes you might be better off with a simple black mask.

The thing that you might not expect about the decals is that you

simply don't see them while playing. The TV display is so much

brighter that it completely overwhelms them to the point of utter

invisibility. Which is exactly what you want, as it turns out: you

want it to look like the backbox of the game you're playing, not like

a TV embedded in a virtual cab. So that works out great, but my point

here is that as far as playing goes, there's no difference between

decals and black paint. And when the cab is powered down, the decals

arguably create the same visual impression that I said I don't

like with the wood cutout approach - the way the visible borders call

attention to what's missing in the middle. But somehow I don't

dislike the look in this flat "2D" version; in person, it actually

looks very much like a real translite, even if it would be a rather

art-impoverished one on a real machine. Even so, a plain black paint

mask would do a better job of hiding the TV cutout when the power's

off; it would just like a solid dark sheet. You could easily

mistake it for a regular translite with really dark graphics that need

some backlighting to come to life.

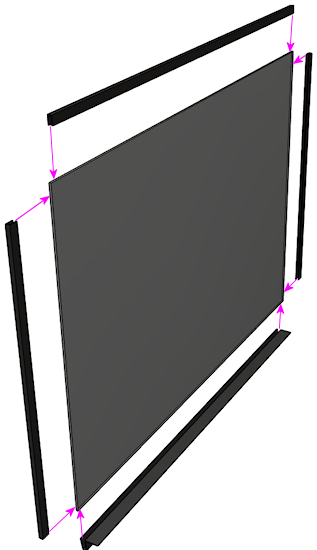

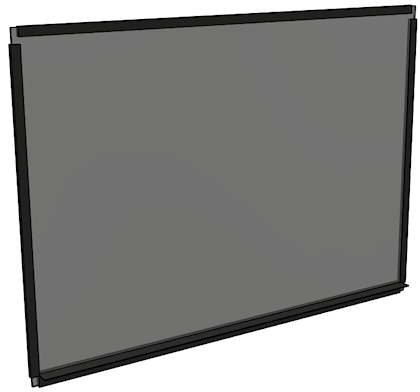

Assembling the trim

The standard WPC translite setup uses four trim pieces around the

edges:

- A "lift channel" at the bottom, part 03-8228-1

- A top trim piece, part 03-8228-2

- Two side trim pieces (one for each side edge), Williams/Bally part 03-8228-2

They're all dead simple to install. Each is a plastic piece with a U-shaped

channel that the glass/plastic sheet fits into. Just align each piece at the

center of its respective edge and press it onto the glass.

Note that the trim pieces don't cover every millimeter of the edges - there's

a little uncovered space at the corners. That's normal.

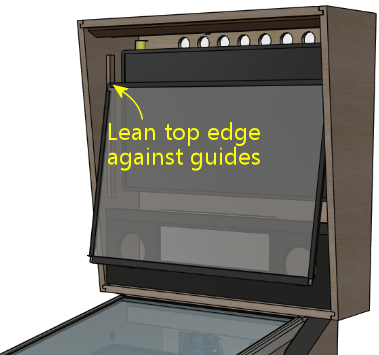

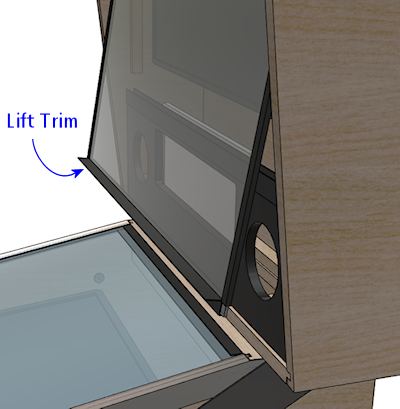

How to install the translite

If you installed a translite lock, make sure it's unlocked, with the

tab turned "sideways" so that it's not sticking out into the top glass

channel. You'll have to use the key to do this. The whole purpose of

the lock is that the tab blocks the channel so that the glass can't be

removed, but this equally well prevents inserting the glass when the

tab is in the "locked" position.

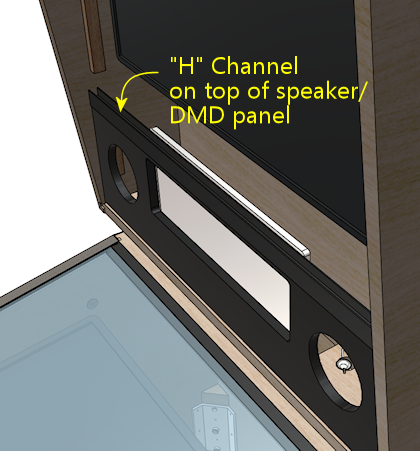

Holding the translite at an angle, lean the top edge against the

guides at either side of the backbox, and slide it upwards into the

slot at the top.

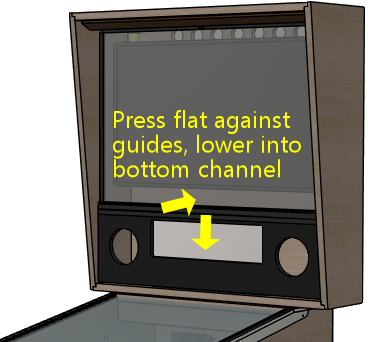

Lift it high enough into the slot that the bottom edge clears the

bottom trim channel. Holding it by the "lift trim" at the bottom,

move the bottom edge forwards until the translite is flat against

the guides, then lower it into the bottom trim channel until it's

seated.

If you have a translite lock, turn the key to the locked position to

secure the translite. Most pinball owners store the key inside the

coin door, hanging it on a little wire hook that's usually located

alongside one of the coin slots.

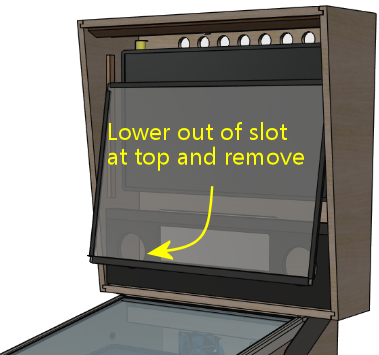

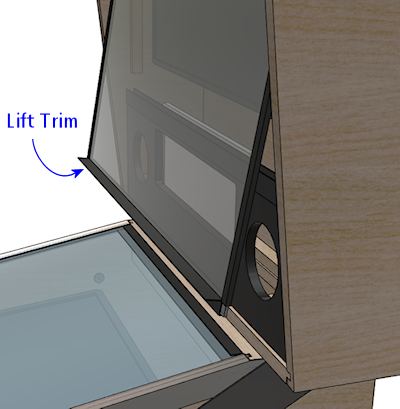

How to remove the translite

If you installed a translite lock, insert the key and turn it to the

unlocked position.

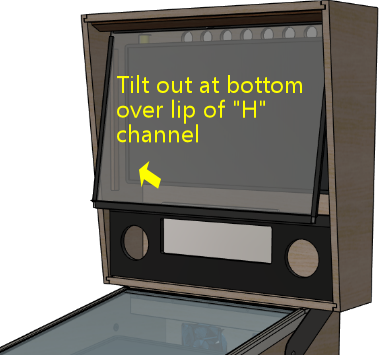

Holding the translite by the "lift trim" at the bottom, slide it

upwards until the bottom clears the lip of the bottom trim channel.

That lets you tilt the bottom outwards.

Now just lower the translite out of the top slot. It's now entirely

free of the backbox trim, so you can remove it.