73. Capacitors

The capacitor is a basic electronic building block that adds a

measured amount of "capacitance" to a circuit, or the ability to

temporarily store a quantity of electric charge.

The ability to store charge makes capacitors look glancingly similar

to batteries, but they're rather different in their physical

construction and electronic properties, and they're used for different

purposes. A battery uses a chemical reaction to store energy, which

allows it to store potentially large amounts of energy over long time

spans. In contrast, a capacitor stores its energy in a standing

electric field, so it can only store a (relatively) small amount of

energy over a short period of time. This makes a capacitor a poor power

source. Instead, the property of a capacitor that's most often used

in circuit design is its ability to resist changes in applied voltage,

which happens because the stored electric field acts as a sort of

buffer that has to be charged up or depleted before voltage changes

can get past the capacitor. This effect can be exploited for purposes

such as signal frequency filtering and power line conditioning.

Types of capacitors

All of the capacitors used in the Pinscape projects fall into one of

two categories: ceramic disc capacitors and electrolytic capacitors.

These aren't the only types that exist - there are about a dozen in

all - but they're by far the most common in everyday electronics.

Most other types are only seen in specialized applications.

Ceramic disc capacitors

These capacitors are usually flat and disc-shaped, but sometimes

they're flat and squarish. Small ones can be bulbous or cigar-shaped.

Ceramic capacitors aren't polarized, so they can be installed in

either direction. There's no "+" or "-" leg.

Disc capacitors tend to have small capacitance values, usually below 1

µF (micro Farad). Common sizes are measured in fractions of a µF,

such as 0.1µF, or in whole nF (nano Farads). Very small ones

are measured in pF (pico Farads).

It's best to keep disc capacitors with their packaging until you're

ready to use them, because they can be so tiny that it's difficult to

read any markings. If you need to identify a disc capacitor, look for

a three-digit number printed on the face of the disc.

For a three-digit number, take the first two digits, and add the number

of zeroes given by the third digit. So for the "154" example pictured

above, we'd take out the "15" and add 4 zeroes, giving us 150000.

This is always a value in pF units - pico Farads, equal to trillionths

(10-12) of a Farad. 1000 pF is the same as 1 nF, so our

"154" capacitor above is 150000 pF or 150 nF, which is also the

same as 0.15µF.

If a letter follows the three-digit number, it's a tolerance code

telling you how precise this measurement is. This is typically K for

±10% or M for ±20%. (You can find tables of these

codes online if you need the full set; search for "disc capacitor

code".)

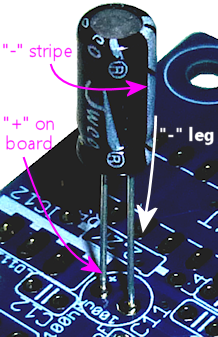

Electrolytic capacitors

Electrolytic capacitors usually come in cylindrical metallic cases as

pictured above. The leads may be "radial" as shown (both sticking out

the same end), or "axial" (each lead sticking out one end of the

cylinder).

These capacitors are polarized, meaning that they're sensitive to the

direction of the voltage applied. One leg has to be connected to the

"+" voltage and the other to the "-" voltage. See the section below

on orientation for help figuring out which leg is which.

Most electrolytic capacitors have relatively large capacitance values,

measured in whole µF (micro Farads). The smallest electrolytics

are around 1µF, and the largest are very large indeed, sometimes

in the hundreds of thousands of µF. (Very large ones might even

be measured in mF - milli Farads - although it seems more common to

stick with the µF units even for very large values.) For the

Pinscape projects, the largest ones you'll see are around

1000µF, which run about an inch tall and half an inch in

diameter.

The capacitance value of an electrolytic is usually printed right on

the case directly, including units, as these capacitors are big enough

physically that there's no need for secret codes. You might see a

label saying "1000µF", for example.

Installing in a circuit board

Most of the capacitors used in the Pinscape project use radial

through-hole leads, meaning that they have two wires sticking out

their bodies, side by side.

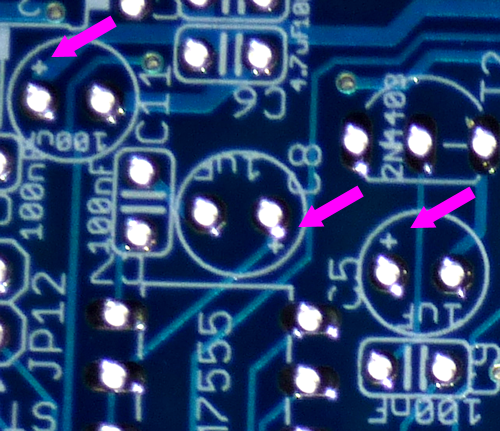

Find the marked spot on the circuit board for the capacitor. It

should show an outline that roughly matches "footprint" of the

part when installed. Then fit the leads through the holes in

the solder pads. Feed the leads all the way through until the

part is nearly flush with the board.

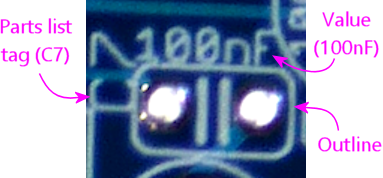

For example, a ceramic disc capacitor is typically shown on the

circuit board with a little rectangular outline:

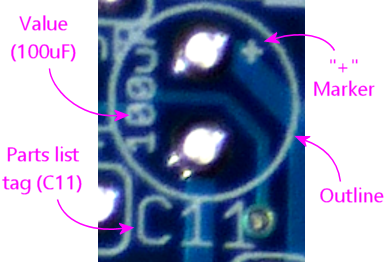

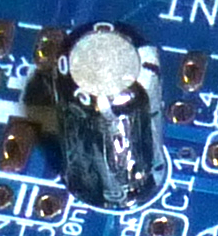

An electrolytic is shown on the circuit board with a circular

outline, with one solder pad marked with a "+" sign to indicate

which way to orient the part:

Orientation

Ceramic disc capacitors are unpolarized, meaning that they don't have

a preferred direction. You can install these in a circuit in either

direction.

Electrolytic capacitors, in contrast, are polarized. They must be

installed in the correct direction. To determine the correct

direction to install one on a circuit board, find the part outline

printed on the board, and look for a little "+" sign printed next to

one of the solder pads:

This is the pad where you solder the "+" leg of the capacitor, so

the other, unmarked pad is for the "-" leg.

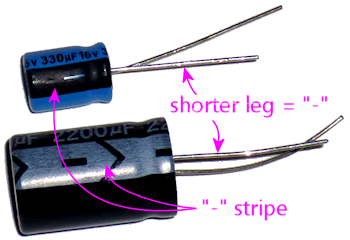

Now look at the capacitor itself. There should be a prominent stripe

painted along one side of the barrel. In most cases, this will be

marked with "-" (minus) signs. The leg closest to this stripe is the

"-" leg of the capacitor. In addition, the legs will usually be

different lengths: the short leg is "-".

Match up the leg on the capacitor near the "-" stripe with the

unmarked "-" solder pad on the board, and match up the unmarked "+"

leg of the capacitor with the marked "+" solder pad on the board.

As with most components, it's best to seat the capacitor close to

the board. There's no need to force anything, but get it as close

as you comfortably can. Solder the leads on the bottom side of

the board, and snip off the excess after the solder cools.

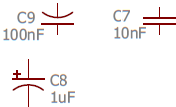

On schematics

Capacitors on schematics are shown with symbols that look like two

parallel lines, or one straight line and one slightly curved line.

For electrolytic capacitors, which are polarized and thus have "+" and

"-" ends, the schematic symbol will show a little "+" sign on the

positive end. If there isn't a "+" sign, it means that an unpolarized

capacitor, such as a ceramic disc type, has to used here.

Capacitors are usually marked with a Cnumber designator,

such as C7 or C9. The "C" is for Capacitor, and the number is

arbitrary, purely to serve as a reference to the parts list. One of

the cardinal rules of schematic writing is that designators have to be

unique in the schematic, so that every part can be individually

identified.

The schematic will usually also show a capacitance value in Farads (F).

This will almost always use one of the following formats:

- 100pF means 100 pico Farads or 100 trillionths of a Farad

- 100nF means 100 nano Farads or 100 billionths of a Farad

- 100uF means 100 micro Farads or 100 millionths of a Farad

Selection

Capacitors have three main specs: the type, the capacitance value in

Farads, and the maximum voltage rating.

Type: In most cases, either ceramic disc or

electrolytic. There are about a dozen other more exotic types

(glass, air-gap, film), but ceramic disc and electrolytic are by far

the most common. They're the only types needed for the Pinscape

projects.

You always have to match the type shown in the schematics and parts

list. If it's not clear from the parts list, check the schematic

symbol for the capacitor: if it includes a "+" sign, an electrolytic

type is needed, otherwise a ceramic disc type must be used.

Capacitance: A value in Farads, almost invariably expressed in

µF, nF, or pF (micro, nano, or pico Farads). Match the value

specified in the parts list or schematic exactly when selecting a

capacitor.

Pay attention to the units - µF, nF, and pF are very different!

1 µF is 1000 nF, and 1 nF is 1000 pF. If you substitute a 1nF

capacitor for one that was supposed to be 1pF, you'll be off by a

factor of 1000; if you substitute 1uF for 1pF, the error is a factor

of a million!

But by the same token, you can take advantage of the factor-of-1000

relationships to figure equivalences. If you're looking for a 0.1uF

capacitor, you can substitute 100nF, since it's exactly the same value

expressed with a different multiplier.

Voltage rating: Every capacitor is rated for its maximum

allowable voltage. This is the highest voltage that it can be exposed

to in the circuit.

If the parts list specifies a voltage rating (e.g., "100uF/50V"), you

must select a capacitor rated for at least that voltage. So if

the parts list says you need a 50V capacitor, you can use a 50V

capacitor, or a 100V capacitor, or anything higher.

If the parts list doesn't specify a voltage rating, it means that the

lowest rated available capacitors (usually 25V) can be used.

Precision: Capacitors are also rated for precision, also known

as tolerance. This is usually given as a percentage, typically 10% or

20%. This means that the manufacturer claims the part will be within

the stated range of its nominal capacitance value. For some

applications, it's critical to be very close to a particular value, so

the engineer who designed the circuit might specify that you need a 5%

or 1% tolerance capacitor in a particular spot. The Pinscape projects

don't have any such requirements, so you don't have to worry about the

tolerance value when selecting parts for these boards.