Appendix 12. Lock Miter I: The Plywood-Friendly Way

The original Williams pinball cabinets of the 1990s used a type of

corner join known as a lock miter. This join has mitered corners

(meaning the ends of the pieces that come together at a corner

are cut at 45°, so that the seam is exactly the corner, making

it practically invisible), plus an interlocking tongue-and-groove pattern on

the inside (that's the "lock" part). There are other good ways to make

the corner joins, but the lock miter is one of the best.

The corners are seamless, the joints are self-aligning and self-squaring,

and they have a lot of internal surface area for strong glue adhesion.

Lock miter corners are also make assembly really easy, since the

corners snap together like jigsaw puzzle pieces.

There are (at least) two ways to make a lock miter join. The first

method, which we'll cover in this chapter, involves making a sequence

of cuts (six steps in all) with a 1/4" straight router bit and a table

saw. I'm covering this method first because it works very well with

plywood, which is what most pin cabs are made of. This method might

look a little intimidating at first, because of the number of steps

involved, but it's actually not that bad. Most of the steps are

pretty simple, and they mostly use natural alignment points that don't

require any arithmetic or ruler measurements.

The second method involves a special router bit that cuts the entire

tongue-and-groove pattern all at once. That's covered in the next

chapter, Lock Miter II: The Special Router Bit Way. That method probably looks easier

at first glance, since the bit does all of the work for you. But

these bits are notoriously difficult to set up properly. There is a

reliable setup procedure, but the time and effort involved in that

ends up making the overall degree of difficulty similar to the more

manual "plywood friendly" method. The real drawback of the

special-router-bit approach is that the tongue-and-groove structures

that the router bits cut are too fine for most plywood, so you

lose a lot of the strength that the join is supposed to provide.

If you're new to woodworking, both methods are probably going to look

like "advanced" procedures that should only be tackled by grizzled

veterans with lavishly equipped wood shops. But don't give up yet!

I'm a woodworking newbie myself, and I've found that both techniques

are doable and can yield great results, even if you're new to this.

I've tried to reduce both methods to straightforward recipes that you

can follow without any special woodworking expertise and with

a modest set of tools.

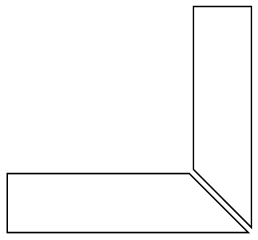

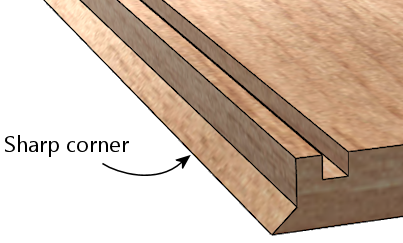

Example of the manual method

Here are some photos of a sample corner built with the manual

method, to give you a better idea of what it looks like.

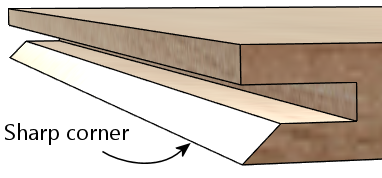

Dry fit of a test corner built using the manual lock miter method.

This is just a couple of scrap pieces that I ran through the process

in this chapter as a beta test. It took about an hour of work;

most of that was spent on the "sneaking up" phase

for the 45° angled cuts. It came out just about perfect -

the two pieces fit together nicely, and the corner is razor-sharp.

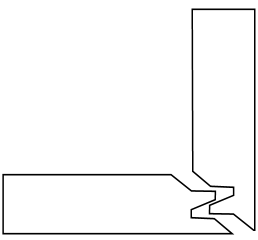

A closeup of the grooves, with the front/back piece on the

left and the side piece on the right.

Another view of the grooves. The thing I like about this

version of the lock miter (the "manual" approach) is that

the tongue-and-groove structure comes out so clean and sturdy

when rendered in plywood, thanks to the relatively large features.

Compare this to the similar pictures of the special router

bit results in Lock Miter II: The Special Router Bit Way).

Pros and cons of the two methods

If you're considering using lock miter corners for your pin cab

project, I'd suggest reading through both methods, so that you can

judge for yourself which one you feel more comfortable with. Here's

a quick summary of what I think are the high and low points of

each approach.

| Router Bit Method | Manual Method |

|---|---|

| Special router bit required ($25-$100+) | Needs only a 1/4" straight router bit (and can be done with just a table saw, no router needed) |

| No table saw required | Requires a table saw |

| Not great for plywood; tongue-and-groove features have poor structural integrity due to small size | Excellent results with plywood, makes a super strong joint |

| Only needs one routing pass over each edge | Six cutting steps required |

| Bit setup is notoriously difficult (but doable if you follow the right procedure) | Fairly straightforward setup for each cut (but there are still six of them) |

I've tried both approaches, and I've found that - surprisingly - the

manual method isn't really any harder or more time consuming than the

router bit method. It might even be a little easier. You'd think

that the special router bits would make things a whole lot easier,

given that they cut the entire pattern in one pass over each edge, but

the complex setup procedure makes up for it. The manual method

involves multiple cuts for each corner, but each one is fairly quick

and easy to set up, and the recipe is pretty reliable at getting all

of the cuts to line up accurately with one another.

Given that neither method has a clear advantage in terms of difficulty

level, my feeling is that the manual method has an edge for a pin cab

project, simply because of its better performance with plywood. The

main obstacle with the manual method for many people will probably be

that it requires a table saw. If you don't have a table saw and you

don't want to buy or rent one, the special-router-bit method is a good

fallback; even though it's not ideal for plywood, it is workable

with at least some plywood.

How the lock miter works

The lock miter is an elaboration of the plain miter join, which is

a simple join where you cut the ends of the two pieces meeting at a corner

at a 45° angle:

The plain miter gives you a nice clean corner without a visible seam,

but it doesn't make a very strong glue joint, and it takes some skill

to execute it well. For one thing, you have to get the two cuts

exactly at 45°, or the corner won't be square. The way the

two pieces meet means that any error in the cut angle of each piece is

doubled in the assembled corner. If you're off by 1° on the cut

angle, the corner will be out of square by 2°. The other thing

that's difficult with a plain miter cut is getting the two pieces to

align correctly during assembly. You have to get the corner aligned

across its whole length, and then keep it there while the glue dries.

There are corner clamp systems that help with this, but it still takes

some skill.

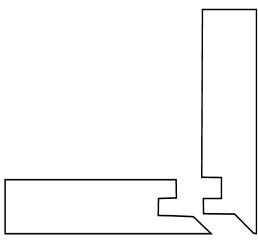

The lock miter improves on this by keeping the 45° angle at the

outside corner and adding an interlocking tongue and groove. There

are different ways to make the interlocking tabs. The special lock

miter router bits produce a pattern that looks roughly like this:

The manual method presented in this section produces this pattern:

The common features are the 45° angled cut at the outside corner,

and the interlocking tongue and groove. Like the plain miter, the

45° angle at the outside makes the corner seamless. The addition

of the locking tabs makes the assembly step almost effortless, since

the pieces can only fit together at exactly the right alignment.

And the extra surface area of the tabs forms a

strong glue joint. This join is also a little more forgiving of

imperfect 45° angles at the corner, since the locking tabs will

still keep the corner aligned and square.

You probably noticed that the router bit method and the manual method

have slightly different shapes for the interlocking tabs. The

differences aren't completely arbitrary. The key difference is that

the tongue-and-groove structures in the manual method are coarser.

That's what makes the manual method perform better with plywood. The

lock miter router bits are forced to use smaller features because

their cutting pattern has to form a mirror image. That's how they

work their magic trick of cutting both sides of a corner join with the

same bit. Every feature has to appear twice, once on each side of the

"mirror", so every feature has to be half-sized. The small

projections are problematic with plywood, in that the glued plies tend

to fall apart when cut so finely. The manual method doesn't have to

be symmetrical, since we make each cut individually. That allows for

larger features, which hold up better with plywood.

Equipment needed for the manual method

1/4" straight router bit: Just to be clear, we're talking about

a bit with a 1/4" cutting diameter (as opposed the shank size - for

that, simply match the shank size your router uses).

Router and router table: If you already have a hand router, you

can buy an inexpensive bench-top router table and use it with your

hand router. Most of the the bench-top tables are compatible with

many brands of routers, so you can generally mix and match tables and

routers. I use a bench-top table from Skil with a Ryobi fixed-base

hand router. The table isn't a high-end piece of precision equipment,

but it works for the pin cab joinery I've attempted.

Router table fence micro-adjuster: Optional but really helpful.

Provides a way to adjust the fence position in tiny fractions of an

inch, to help get the alignment perfect. This is something you can

make yourself as a simple DIY project described later in this chapter.

Table saw: For the 45° angled miter cuts.

1/4" MDF scraps: For use as alignment aids. You just need a

couple of scrap pieces, roughly 6"x6" and 2"x6". 1/4" plywood or

hard-board will also work.

Auxiliary fence for your table saw: A piece of 3/4" MDF or

plywood, cut to about the same size as your table saw's fence.

Doing it all with a table saw

You can create a lock miter using just a table saw, no router

required. You need a 1/4" dado stack in place of the 1/4" router

bit used in my procedure.

The steps in my procedure are tailored to the router table, so you

might want to look for a recipe that's specific to the table saw -

there are some equally complete table-saw versions out there. Search

the Web and/or Youtube for lock miter with table saw.

Or you could just adapt my recipe, if you don't mind puzzling out how

to translate the router fence alignment steps to the table saw. The

alignment points for the cuts are all the same relative to the boards,

so it doesn't take much translation. The main thing to watch out

for is that you'll need an auxiliary fence for a couple of steps,

since the saw blade will otherwise be too close to the main fence.

Do a practice run

This is a complex enough procedure that I felt the need to do a couple

of practice runs on scrap material before I tried it for a real

project. You might not need to, but I found it helpful as a

confidence booster, to make sure I understood all of the steps.

The other nice thing about a practice run is that it helped me

fine-tune my sense of the various alignment points. The procedure is

designed to make the alignment points easy to judge, but even so,

there's always a little wiggle room when trying to get two things to

line up. If anything comes out a little off in the test run, you can

use that as a guide to compensate the next time through.

Preparation

Get all of the panels ready: Wait until all of your panels are

cut to final sizes before starting the lock miter procedure. You

should do all of the lock miter routing across all panels at the

same time, so that you only have to do the setup part of each step

once.

I'd do the lock miter cutting on all panels before routing

other features (e.g., floor dados), drilling holes (flipper buttons,

say), and cutting openings (like the coin door cutout). The panels

are easier to handle whole.

Include a scrap "side" and "front" piece for testing every cut.

Reserve a small scrap piece of plywood for each, designating one as

"side" and one as "front". Make each cut on the corresponding scrap

piece first as a sanity check that you're set up correctly. This is

especially helpful in the steps where you have to "sneak up" on the

final alignments with a series of test cuts. The idea with "sneaking

up" is that you start with a cut that's intentionally shy of the real

cut line, then you check how close you got, and then gradually re-cut

closer and closer until you get exactly to the right spot. I

sometimes make the mistake of overshooting the final cut line because

I wasn't gradual enough in the re-do cuts. It's nice to know that

you're only ruining a piece of scrap if that happens.

Pre-mark all panels. The lock miter we're doing involves two

different cutting patterns, one for the side panels, and a

different one for the front/back panels. It's crucially important

that you cut the right pattern in each panel. To avoid switching

things around in the heat of battle, mark each piece conspicuously

before you start, to indicate whether it's a SIDE or

FRONT/BACK piece. I also like to mark the INSIDE and

OUTSIDE face of each piece so that I don't have to think about

that later. The inside/outside orientation matters for every cut. I

make all of these markings right along each edge where the lock miter

pattern goes, just beyond the cutting area (about 3/4" from the edge),

to help make sure I'm cutting the correct edge. I don't want to have

to think too much while the router is running - less chance of

screwing something up.

Install a 1/4" straight bit in your router. This bit will

be used for all routing throughout the procedure.

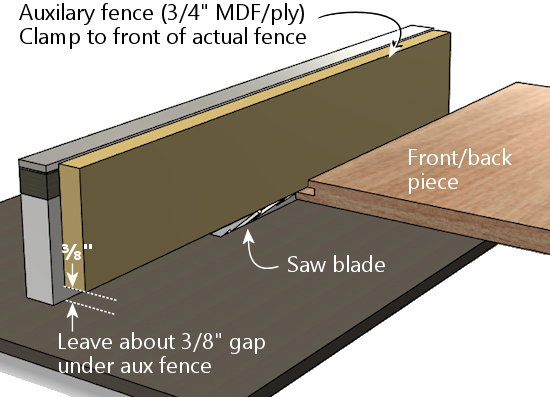

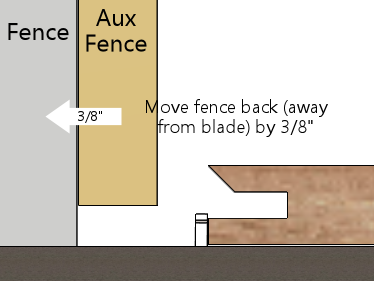

Set up an auxiliary fence for your table saw. Simply cut a

piece of 3/4" MDF or plywood to roughly the same size as your saw's

fence, and attach it to the blade side of the fence with clamps, with

the bottom of the aux fence about 3/8" above the table top.

A few tips, tricks, and precautions

Always unplug the router before adjusting the bit height or

fence position.

Make multiple router passes for grooves deeper than 1/4".

Router bits work best doing a little at a time. For deep grooves,

start with a first pass at 1/4" deep, then repeat at 1/2" deep, and so

on until reaching the target depth. Don't move the fence between

passes - only change the bit height.

Take a close look at your router bit and notice how it's not

perfectly round - it probably has a slightly oval shape, with cutting

edges that stick out slightly. When you're aligning something with

the outside of the bit, you want to make sure you're using the widest

part of the cutting edge as the reference point, since the bit will

remove material out to the widest point.

Table a close look at your table saw blade and notice how the

teeth are a bit wider than the main disk. When aligning an edge with

the saw blade, you always want to align with the widest point of the

teeth, since the cut line will go out that far.

To avoid tear-out at the end of each cut where the router bit

exits the board, try putting some masking tape along the trailing

edge. If that doesn't work, use a scrap piece of the same 3/4"

material, and keep it pressed up against the trailing edge as you push

the end of the real work piece past the bit.

Cutting steps

The cutting procedure works by aligning each cut with a previous cut.

I've tried to provide an easy method to hit each reference point

without any guesswork. At each step, I'll explain the goal we're

trying to accomplish, and then give you the method I use to accomplish

it. Each step also starts with a schematic diagram showing the

goal, but don't worry about trying to puzzle out the setup from

the schematic - it's just there so you can see what the step's

cut will look like and how it fits into the overall pattern.

Several of the steps have a setup procedure and a test

procedure. The test procedure in each step is optional, so feel free

to skip that part if it feels too tedious. The setup steps alone are

pretty reliable. But I find that the extra test-and-adjust steps

help me get the alignments closer to perfect.

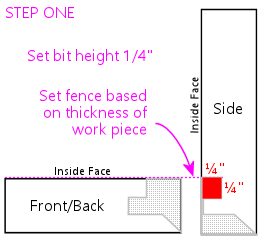

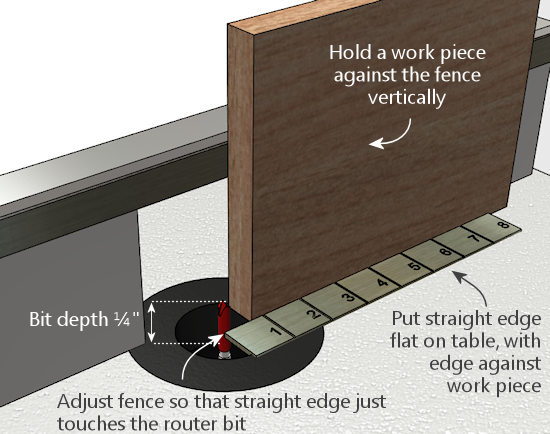

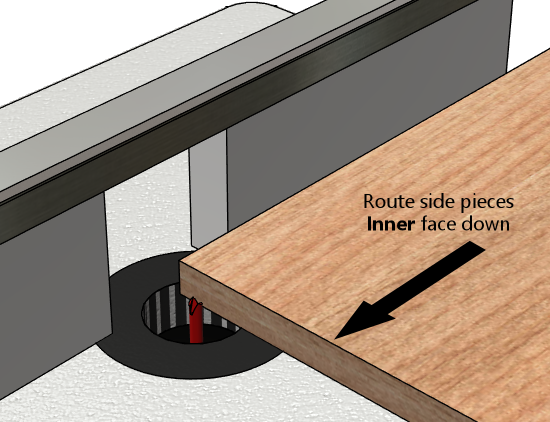

Step 1: Inner groove on the side pieces. This groove

has to align with the inside face of the front/back piece, so we'll

use the thickness of a sample work piece as our alignment guide for

the fence. The bit height is simply 1/4".

Set the bit height to 1/4" above the table, using a ruler or other

measuring tool of your choice. (For better precision, use good set

of calibrated setup bars - search for router setup bars on

Amazon.)

To position the fence, place one of the work pieces against the fence

vertically. (It doesn't matter which piece - all we care

about here is the thickness, which is the same for all work pieces.)

Make sure to keep it tight against the fence. Place a straight edge

flat on the table along the edge of the work piece, with one end

extending out so that it's alongside the bit. Adjust the fence so

that the bit just barely touches the straight edge. Rotate the bit

back and forth to make sure that you're testing it at the widest

point.

This is a good time to deploy the

fence micro-adjuster, to

help get the alignment perfect.

The alignment on this step is pretty important, so if you want to be

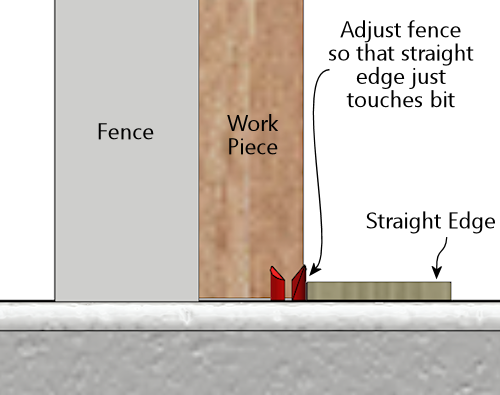

extra-careful, you can run a quick test. Take two scrap pieces (from

the same plywood as the real pieces, of course), lay one flat, and

stand the other one up alongside it as shown below. Mark a line on

the vertical piece using the horizontal piece as a straight edge.

Route just an inch or so of the marked piece (line facing down and

towards the fence), and check that the groove is exactly up against

the line. It shouldn't cross the line or cut into the line - it

should leave the line intact and just touch it with exactly zero

clearance. If it's a little off one way or the other, use the

micro-adjuster to compensate, and test it again.

Once you're set up, it's time to the do the actual routing

for this step. Route each SIDE piece, with the INSIDE FACE down.

Remember to route both ends of each side piece, for the joins

at the front and back.

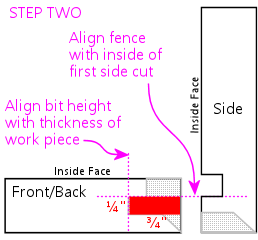

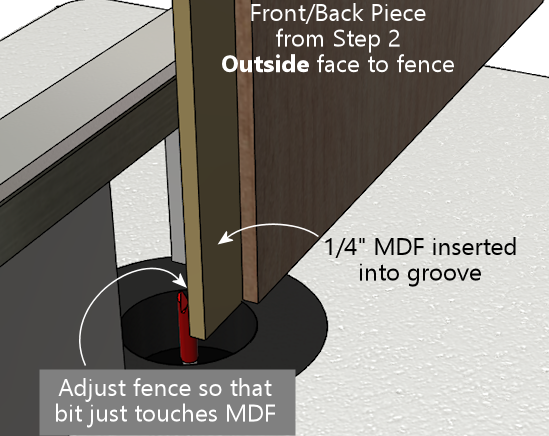

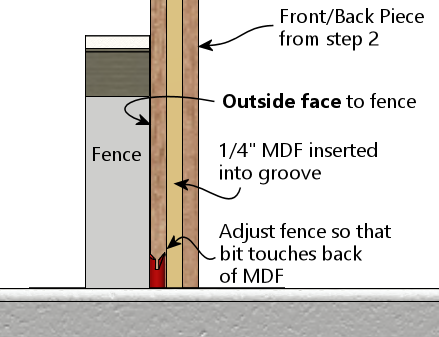

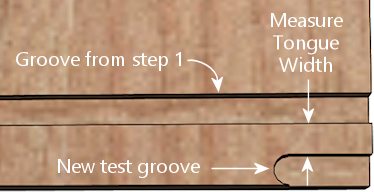

Step 2: Cut the center groove in the front/back pieces. The

groove's depth has to equal the thickness of the work piece, so we'll

set the bit height based on a sample work piece's thickness. The

inside of the groove has to align with the outside of the side groove

from step 1, so we'll set the fence position using the actual groove

in one of the side pieces as a reference point.

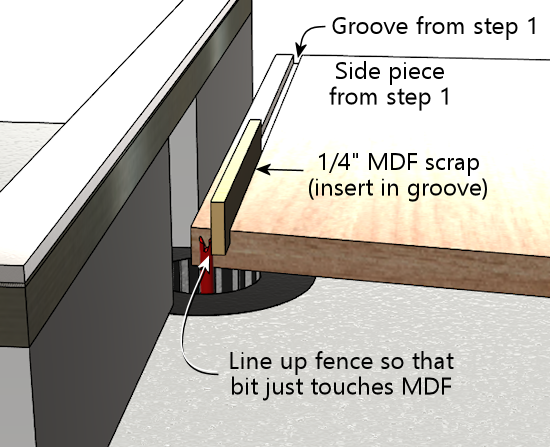

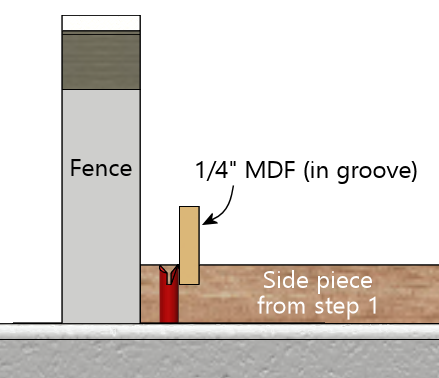

Grab one of the side pieces you just cut and fit a piece of 1/4" MDF

scrap into the groove as shown below. Place it on the router table

with the edge against the fence. Set the fence so that the bit just

touches the MDF.

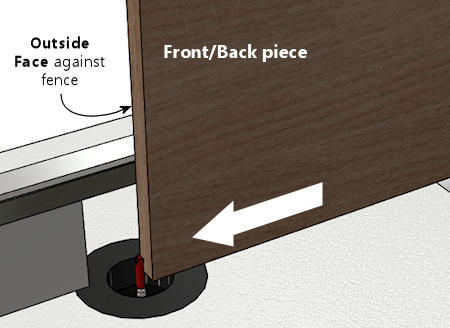

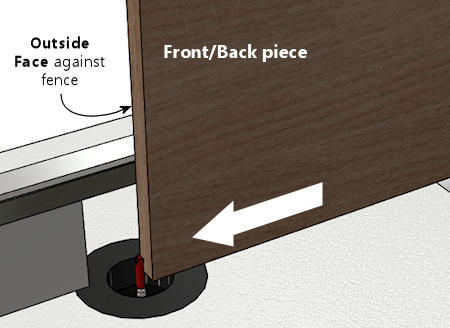

Here's how we're going to do the routing for this step. Route the

FRONT and BACK pieces vertically against the router

fence, with the OUTSIDE FACE to the fence. But we're not

quite ready yet - we might want to check the alignment first, and we

still need to set the bit height.

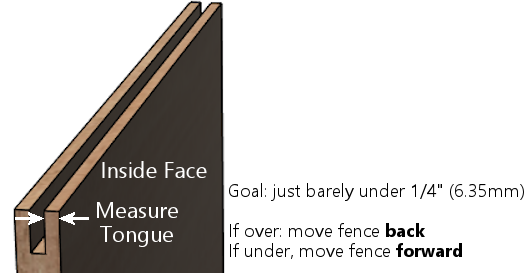

If you want to check the alignment to make sure it's right, there's a

quick test that you can do before proceeding. Set the bit height to

about 1/4" above the table, grab a scrap testing piece, and route it

as shown above. This is just a test cut, so you only need to go an

inch or two. Now measure the width of the "tongue" on the

inside face, as illustrated below. I find digital calipers are

the easiest way to get a precise reading here. The thickness should

be just a hair under 1/4" (6.35mm) thick. Something like 6.2mm to

6.3mm is perfect. This tongue slots into the 1/4" groove from step 1

when you assemble the corner, so it can't be any thicker than 1/4", or

it won't fit the groove. It's best if it's just the slightest bit

thinner than 1/4", so that it fits easily but snugly. A looser fit

isn't a disaster, but it won't be as strong when assembled, and it

might not self-align as perfectly. If you're using the fence

micro-adjustor, you can use the measurement to figure out how many

turns of the screw are needed to get it exactly to a target of, say,

6.2mm. In any case, if you make an adjustment, I'd repeat the test

(in my case, because I'm 50% likely to go the wrong direction, even if

I'm looking straight at these instructions).

| Measured Width | Make This Adjustment |

|---|---|

| Over 1/4" | Move fence back (away from bit) |

| Under 1/4" | Move fence forward (towards bit) |

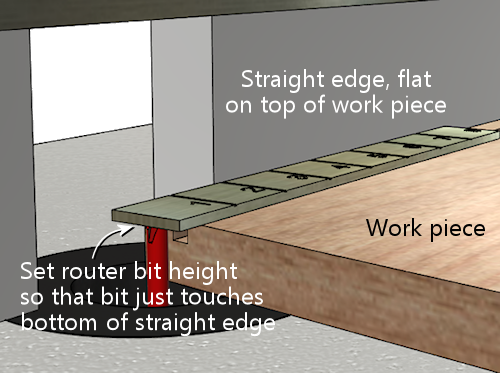

Now we're ready to set the bit height. This is a deep enough groove

that it's best to route it in multiple passes, so that we don't try to

force the router bit through too much wood at one time.

- First pass: bit height set to roughly 1/4" above the table

- Second pass: bit height set to roughly 1/2" above the table

- Final pass: calibrate to the work piece thickness

For the final pass, calibrate the bit height to match the thickness of

the work pieces by placing a work piece flat on the table alongside

the router bit. Adjust the bit height so that it matches the plywood

thickness (or just a hair beyond). A straight edge on top of the

work piece can help get it perfectly aligned.

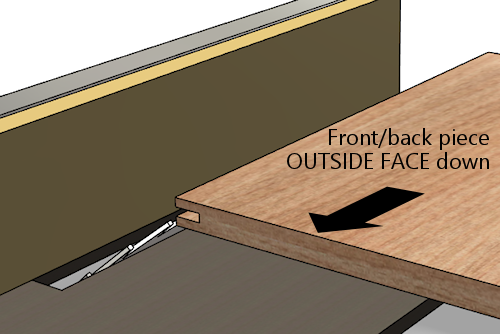

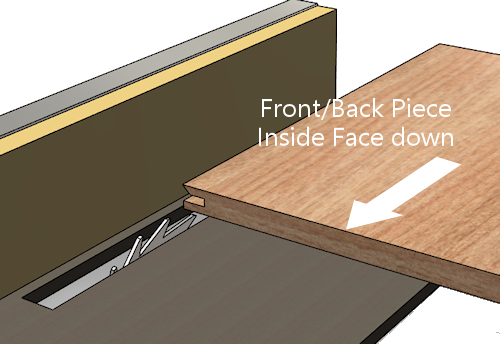

For each pass, route as shown in the illustration we saw earlier:

route the FRONT and BACK pieces vertically against

the router fence, with the OUTSIDE FACE to the fence.

Here's the illustration again:

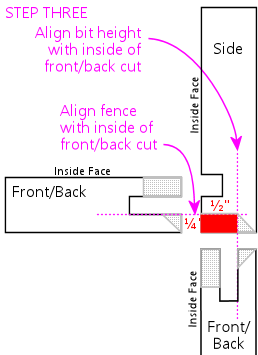

Step 3: Outer groove on the side pieces. This step finishes

the "tongue" on the side pieces. The fence position for this cut has

to align with the outer side of the front/back groove from step 2, so

we'll use a front/back piece from the previous step as a reference

point. The bit height has to align to the leftover portion outside

the groove from step 2, so we'll also use a front/back piece as a

reference for that.

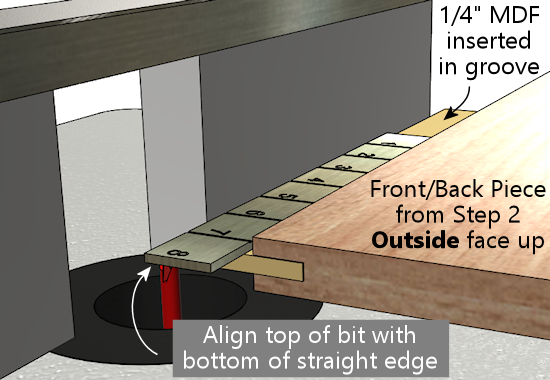

Take a front/back piece from step 2, and insert a scrap piece of 1/4"

MDF into the groove. Stand this vertically against the router fence

with the OUTSIDE face of the front/back piece against the

fence. Place it so that the MDF extends just past the bit.

Adjust the fence so that the router bit just touches the back

of the MDF.

This is another deep cut that's best done in two passes - first at

1/4" deep, then at full depth. So set the bit height to 1/4"

above the table for the first pass, route all of your side

pieces, and then set the final bit height as described below.

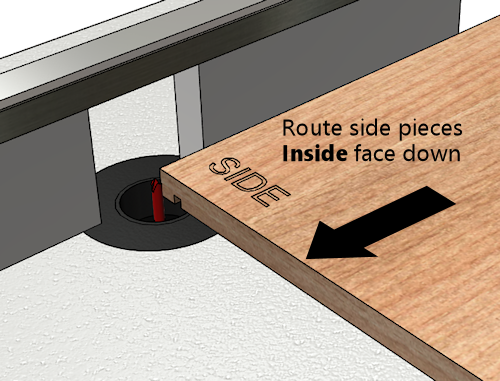

Here's how we're going to do the routing: SIDE pieces, flat

against the router table, INSIDE face down.

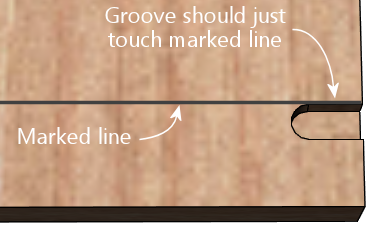

Before routing your actual side pieces, though, you can do a quick

test to check the fence alignment. You'll need the scrap "side" piece

from step 1, that already has the 1/4" wide by 1/4" deep groove set in

1/2" from the edge. Do the test on that piece. Route it as shown

above, but you only need to go for an inch or two for this test.

Now measure the width of the "tongue" between the two grooves:

It should measure just under 1/4" (6.35mm). This part has to fit

into a 1/4" groove, so if it's more than 1/4" wide, it won't fit.

You don't it to be too loose, either, so the ideal is something

just under 1/4", perhaps 6.2mm to 6.3mm. If it's too wide, move

the fence back (away from the bit); if it's too narrow, move

the fence forward (towards the bit).

| Measured Width | Make This Adjustment |

|---|---|

| Over 1/4" | Move fence back (away from bit) |

| Under 1/4" | Move fence forward (towards bit) |

Once you're satisfied with the fence alignment, route all of the side

pieces as shown above, keeping the bit height set at 1/4" above the

table. Once done, you'll need to make one more pass over all of the

pieces at the final bit height.

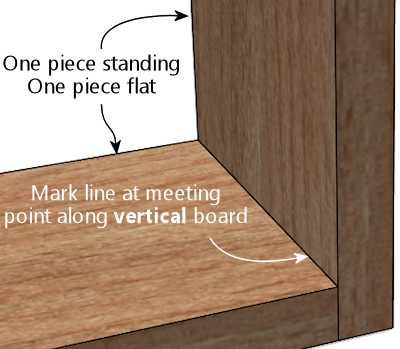

To set the final bit height, use a front/back piece with a piece of

1/4" MDF inserted into the groove. Put the whole thing flat onto the

router table as shown below, with the OUTSIDE FACE facing up.

Put a straight edge on top of the MDF so that it extends out over the

bit. Adjust the bit height so that the top of the bit just touches

the bottom of the straight edge.

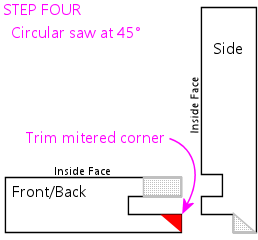

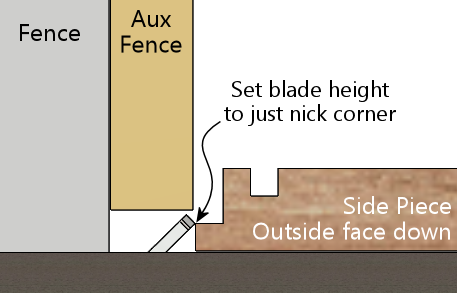

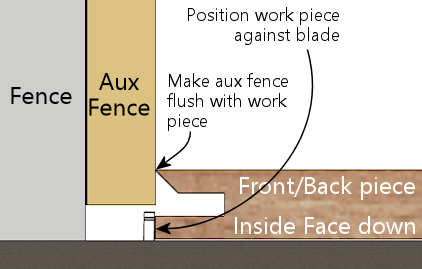

Step 4: Cut the 45° miter on the front pieces.

This step (and the rest of the steps) are on the table saw.

First, set up an auxiliary fence on your table saw. This is just a

piece of 3/4" MDF or plywood, cut to about the size of the fence, and

clamped to the front of the fence. Leave a gap of about 3/8" between

the bottom of the auxiliary fence and the table top, to make room for

the blade to extend 1/4" above the table.

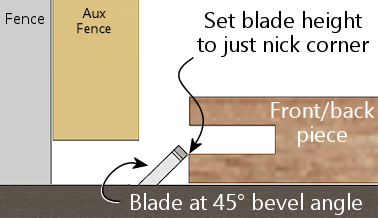

Set the saw blade to 45°. Adjust the height so that the

blade just nicks the corner of the tongue in a front/back piece,

as illustrated below.

This cut needs to be precise, and I haven't found an easy trick like

in previous steps to align it with another cut. The best approach I

can come up with is to "sneak up" on the final cutting position with a

series of test cuts. The good news is that you only have to do a

series of test cuts for one piece. Once that one piece looks perfect,

just run the rest of the front/back pieces through the saw with the

identical fence position, and they should all come out equally perfect.

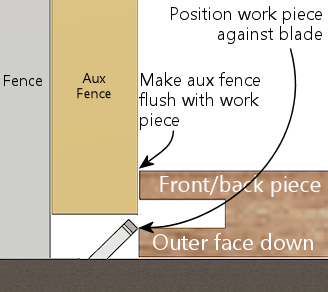

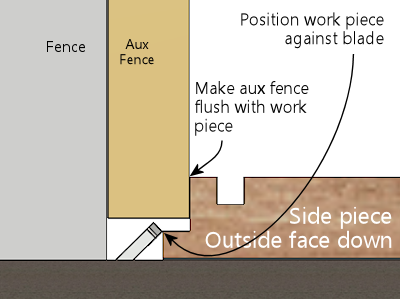

Start by positioning the fence to remove no material at all, by

pushing the work piece right up against the blade, and making the aux

fence flush with the work piece:

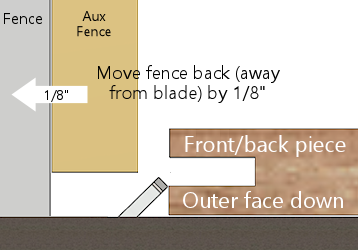

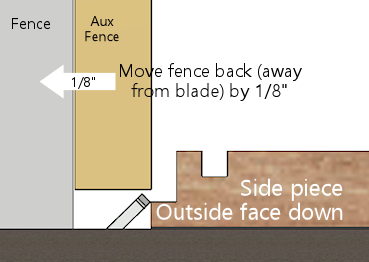

Now move fence back (away from the blade) by about 1/8".

When you move the work piece back behind the blade and push it

up against the fence, the bottom corner of the work piece should

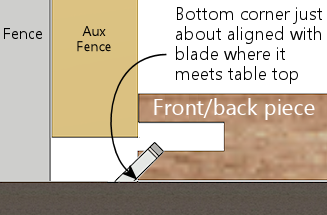

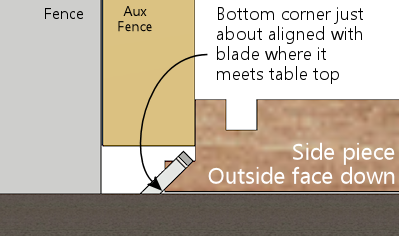

now just about line up with the saw blade:

Double-check by eye that the blade is aligned as shown. Remember,

it's best to remove too little material at this point than too

much, since we can adjust things and take off a little more if we have

to. That's why we only moved the fence 1/8", even though the ultimate

target is closer to 1/4". If it looks like the blade is already going

to hit the bottom corner, move the fence a little further towards the

blade to open up a small gap.

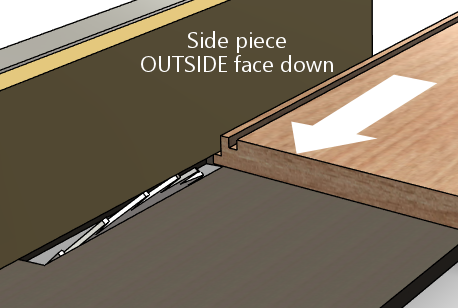

Do a test cut, with the front/back piece OUTSIDE FACE down.

Tip: after each fence adjustment (including the first one), initially

only run the first few inches of the board through the saw, and

inspect the result to make sure the fence isn't already too back. If

the fence is too far back, you'll be cutting material off the outside

face of the outside edge, which you don't want to do. When this

happens, you'll see a little indent along the outside edge where

material was cut off. The goal is to get the 45° cut exactly

up to the outside edge of the outer face without actually cutting

any material off the outer face. Making a partial cut lets you see

immediately if you've gone too far, since the outside edge will no

longer be a straight line. You can't undo this, which is why I like

to include a scrap piece in every batch for these first cuts while

adjusting the fence.

When it's exactly right, you should have a sharp outside corner.

If the corner is still a little squared, you just need to adjust

the fence back slightly (away from the blade) and try again.

Make small changes to ensure you don't overshoot. Repeat

until the corner is sharp.

You can now run all of the remaining front/back pieces through.

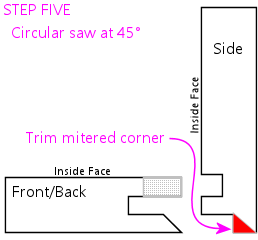

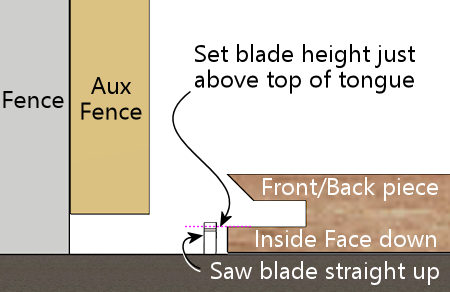

Step 5: Cut the 45° miter on the side pieces. This is

essentially the same as step 5, just with a different blade position

to match the side pieces this time.

You should be able to keep the same blade height from the previous

step, but check it with a side piece to confirm.

Adjust the fence position using the same drill as last time. Start by

pushing the work piece up against the blade, and making the fence

flush with the work piece:

Now back the fence away from the blade by about 1/8".

Move the work piece behind the blade and flush with the fence, and

verify that the blade isn't quite going to cut hit the bottom corner.

As before, it's better to cut too little at this point, since we can

re-cut a little more if necessary.

Do a test cut, with the side piece OUTSIDE FACE down.

As before, we're looking for a nice sharp corner.

If the corner is still a little squared, adjust the fence back

slightly (away from the blade) and try again. Make small

changes to avoid overshooting. Repeat until the corner is

sharp.

You can now run all of the remaining side pieces through.

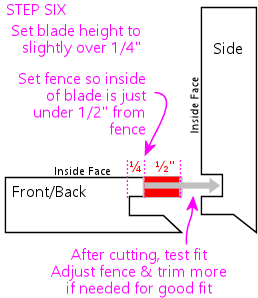

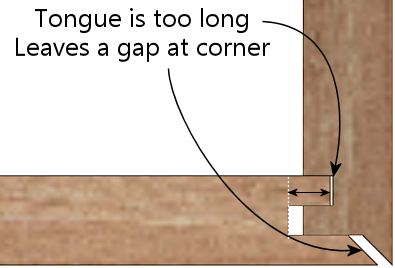

Step 6: Trim the tongue on the inside of the front/back pieces

so that it fits into the side slot from step 1.

I do this step last because it's another "sneak up" cut, and doing

it last lets us test to see if we trimmed enough off by doing an

actual test fit. That's the best test for exact alignment.

We'll use the table saw for this cut. Set the blade so that it's

straight up. Position a front/back piece on the table next

to the blade, inside face down. Adjust the blade height so

that it's just above the top of the tongue - about 1/4".

Put the work piece flush against the saw blade, and move the fence

so that it's flush with the work piece.

Now back off the fence, away from the blade, by about 3/8".

Since we have to "sneak up" on the final fence position with test

cuts, just do one edge of one front/back piece at first. We'll test

the fit and adjust as needed before running the other pieces.

Run a FRONT/BACK piece through the saw, INSIDE FACE

down.

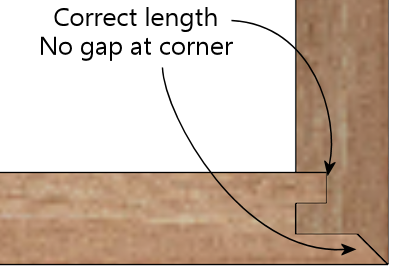

Test the fit against a side piece. The two pieces should fit together

at the outside corner without any gaps. If the tongue in the

front/back piece is jutting out and preventing the pieces from fitting

together, we need to trim it back a little more. Back the fence away

from the blade - just slightly - and do another test cut. Repeat

until it's a good fit.

Once you have a good fit with one piece, finish the remaining

FRONT/BACK pieces.

That's it - you're done! The corners should all fit together tightly.

If any of them are so tight that you have to force them together, try

manually sanding the sticking points.

Router fence micro-adjuster

Table saws usually come with rack-and-pinion fences that you can

adjust fairly precisely by turning a knob. Router tables, in

contrast, usually have much simpler fences, without any adjustment

mechanism at all. The fence usually just slides freely on a couple of

parallel tracks. You move it by hand to where you want it, then

tighten some knobs that hold it in place.

That's not a very precise way of positioning the fence, but it's good

enough for most applications. There are tasks where you can really

benefit from more precise positioning, though. Lock mitering is one

of them.

There's a solution, and it doesn't even require spending a fortune on

a super-deluxe router table. You can make a really simple

micro-adjuster for your existing router table fence. You don't have

to make any permanent modifications to the router table, and you can

build the micro-adjuster out of scrap wood and hardware you probably

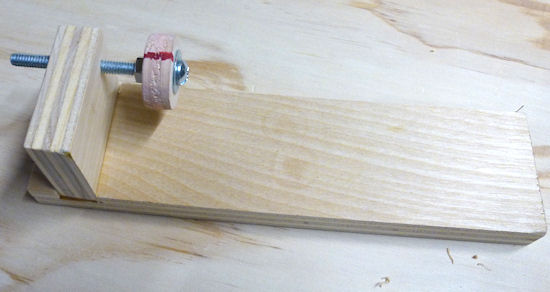

have lying around. Here's the one I built:

The wood is all 3/4" plywood, and the two pieces are simply glued

together at a 90° angle. (I routed a shallow 3/4"-wide dado

that the vertical piece slots into, which makes the glue joint

nearly unbreakable.) The screw is a 3" long, 1/4"-20 machine

screw. In the vertical plywood piece, I drilled a hole slightly

smaller than 1/4", and then worked the screw in so that it cut its own

threads into the wood.

I added a DIY knob, in the form of a "donut hole" cut out of 3/4"

plywood using a 1" hole saw. (There's a KEPS lock nut on the inside

to keep it in place.) I drew a big red mark so that I could easily

gauge full turns, half turns, quarter turns, etc. Alternatively, you

can buy a plastic knob at Home Depot or Amazon, or skip the knob

entirely and make adjustments with a screwdriver.

The micro-adjuster is simple to use. First, set up your fence as

close as you can get "by hand" to where you want it. Second,

tighten the knob-screw on one side to pin the fence down on that end.

Third, position the micro-adjuster behind the fence on the

other side (the un-pinned side), with the screw just touching

the back of the fence. Clamp the adjuster to the router table so that

it stays put at this position. You can now tighten the fence knob on

this side to fix the fence position here.

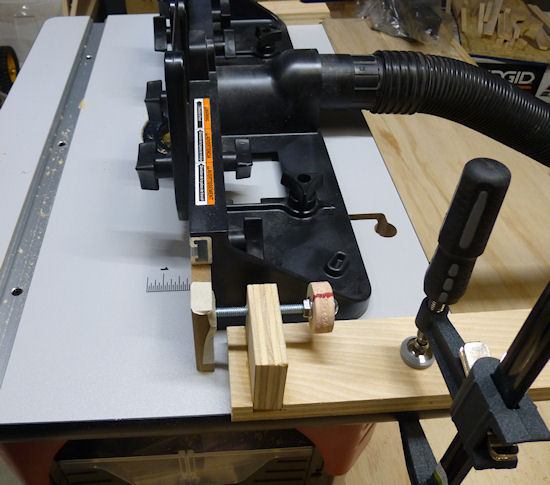

The micro-adjuster as deployed, sitting behind the fence on my router table.

It's simply clamped onto the table with an F-clamp.

My fence is MDF, so I masking-taped a penny to the back where the screw

contacts the fence, to make a harder contact point and prevent

the screw from making a divot in the MDF. Note that I also

clamped a small wood block behind the fence on the opposite

side to set a hard stop, to ensure that the fence can't slip back even slightly on that side. The fence

already has a knob that locks it down on each side, but I wanted to ensure

that there's absolutely no slippage when we micro-adjust the micro-adjuster side.

Now you can make tiny, precise adjustments to the fence position.

When you need to move the fence by a tiny amount, loosen the fence

knob on the micro-adjuster side only, and turn the screw in the

appropriate direction to move the fence forward or back. When moving

it back, you'll have to push the fence against the screw, since the

screw won't pull it back on its own, but the adjustment should

nonetheless stay very precise as long as you keep the fence pressed

against the screw.

If you're using a 1/4"-20 screw like I am, each full 360° turn of the screw

corresponds to 1/20 of an inch change in the fence position. (That's

the "-20" in 1/4"-20 - it means that the screw has 20 threads per

inch.) With a knob, it's easy to gauge a quarter turn, which

corresponds to 1/80 of an inch, or even an eighth turn for 1/160".

What's more, that's the distance the

screw moves. The thing that matters is how far the center of

the fence moves, since that's where the bit is. The center of the

fence only moves half as far as the screw, since the screw is at one

end and the other end is kept fixed in place. So an eighth turn on

the knob equals 1/320" of travel at the center of the fence. That's

plenty of precision for anything I've ever attempted.

You might wonder how we keep the fence "square" if we're only moving

it at one end. Moving just one end obviously will cause the fence to

angle slightly on each adjustment. If this were a table saw, that

would be a huge problem. But it's okay with a router table! The

difference is that router bits are round, so there's really nothing to

be "square" to. (Okay, technically, table saw blades are also round,

but a saw blade defines a plane that the fence must be parallel to.

There's no equivalent parallel plane for a router bit, so it doesn't

matter how the fence is angled.)