29. Playfield TV Mounting

This section is about how to install the main TV - the one that takes

the place of the playfield.

This section tries to address the two big questions about installing

the TV. The first is where to position the TV in the cabinet, which

is as much a matter of aesthetics as of function. The second

is the engineering question of how to physically attach the TV to the

cabinet, once you've figured out where you want it.

Where to place the TV is one of the top questions that new cab

builders ask on the forums. It's one of those things that seems

self-evident at first glance, but has a lot of subtlety when you look

more closely. It's obvious that the TV has to lie on its back near

the top of the cab, but that doesn't quite answer the question, since

it leaves a few inches to play with to move the TV up and down and

front to back. Those few inches can make a lot of difference

aesthetically - it's that matter of what exact positioning is

ideal that raises all of the forum questions. This chapter surveys

the options and their respective pros and cons. I have some opinions

about what looks best, which I'll share, but I'll also try to give

equal time to the alternatives. I don't think there's a single right

answer, because everyone has their own priorities for their cab and

their own sense of what looks best.

After the survey of positioning alternatives, this section presents my

attempt at an all-purpose, universal TV mounting system. When I was

building my own cab, I found the TV mounting to be one of the more

challenging problems. The TV makers don't expect you to use a TV like

this, and the people who make pinball machines don't think of putting

a TV inside, so neither world gives us an example we can look to for

ideas, and neither world offers a ready-made hardware solution we can

apply. Every cab builder has always been on their own to work out

their own unique, ad hoc scheme. That always seemed like a waste of

energy to me; I've always thought there should be at least a basic

template we can follow. I think I've managed to come up with

something like that. This chapter provides a general-purpose design

that should be flexible enough to work with most TVs and most cabs,

using standard parts that you can readily buy. It's at least an

option to consider, and even if it isn't a good fit for your cab, it

might still give you some ideas to draw on. If you're looking for

even more ideas, at the end of the chapter, I'll outline a few

alternative mounting schemes that other cab builders have used.

We're assuming here that you've already picked out a TV to install.

If you're still shopping for a TV, there's a separate section with

advice about that, Selecting a Playfield TV.

Orientation

The playfield TV is always installed in "portrait" mode, to fit

the proportions of the cabinet. This represents a 90°

rotation from the standard way you view a widescreen TV.

But should it be 90° clockwise or 90° counter-clockwise?

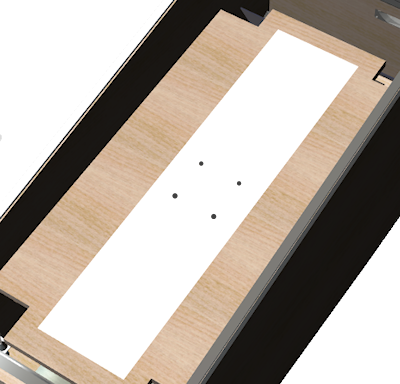

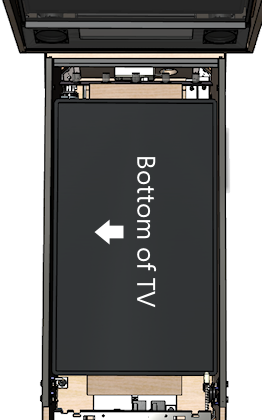

Most virtual cab builders install it with the bottom of the TV

facing left in the cab:

In principle, it really shouldn't matter. Windows and all of the

pinball software should let you select whatever rotation you

want. But this is one of those cases where you can save yourself some

hassle by doing it the same way everyone else does it. There's still

a lot of older software in use in the pinball ecosystem, and some of

it might not be as adaptable as modern programs. I don't know of any

actual examples of software that will outright fail to work with other

rotations, but I know from helping people out with PinballY that

monitor rotation in general can cause configuration headaches,

especially with some of the commercial games.

Positioning options

Before we get to the mechanics of installing the TV, let's consider

exactly where you want to position it. To a first approximation, of

course, it goes "where the playfield goes". But a TV isn't quite the

same as a regular playfield, in either its nature or its size and

shape. So saying that the TV goes where the playfield goes is too

vague to constitute a plan. It leaves a couple of important

questions unanswered:

- Should the TV screen be flush with the top glass, or set in a bit like a real pinball machine's playfield?

- Should the TV be all the way at the front, flush with the lockbar, or should you set it back a few inches to make room for a plunger?

Judging by how often these questions come up on the forums, many

new cab builders agonize over these quite a bit.

I want to offer some thoughts about how to decide these questions.

Most new cab builders focus on how the placement will affect

playability. That's certainly the right priority. But the

thing is that playability actually won't be much affected, no matter

what TV positioning you go with. When you're playing, your eye adapts

to whatever setup you have, and before long you won't even notice it.

It's the same principle that makes the curtains around a movie theater

screen disappear once the film starts rolling. When you're playing,

it doesn't much matter where the TV is relative to the rest of the

cab. All of that disappears; your eye pays attention to the table.

This should be reassuring if you're been agonizing over the question,

because it means that you'll likely be happy with your cab's

playability no matter what you decide.

TV placement can make a big difference to the aesthetics of the cab,

though. Since playability isn't much of an issue, I think the

aesthetics are the better focus when making these decisions. In

addition, there are some functional considerations, since the TV

placement affects the space layout inside the cabinet. You might have

space constraints that decide some of these variables for you, before

you even get to think about how it'll look.

The dreaded plunger space conflict

See also "Positioning the plunger" in Plunger.

One of the key space constraints that affects TV placement is the

plunger. This is an issue because the most natural placement of the

TV and of the plunger put them into conflict: they both want to

occupy the same space.

The natural place for the TV is all the way at the front of the

cabinet. The natural place for the plunger is where it goes on

the real machines. The problem is that the plunger sticks into

the cabinet by about 3", so if the TV is all the way at the

front, it overlaps the plunger.

Why isn't this a problem on the real machines? In part, it's because

the plunger sits just above the playfield on a real machine, so

they're in different planes vertically and thus don't collide. In

addition, on the real playfields, they cut a notch out of the

playfield at that corner specifically to make room for the plunger.

That lets you lift up the playfield without hitting the plunger.

If we could cut a notch out of the TV, we could solve this the

same way, but that's not really an option. Our options all involve

moving either the TV or the plunger to make room for the other:

- Move the TV down a couple of inches to clear the plunger. I don't think I've ever heard of anyone doing this; I think it would put the TV lower than anyone wants it. In addition, you'd now have the problem that the plunger sticks out visibly above the TV, so you'd have to do something to cover that up.

- Move the plunger upwards far enough to clear the TV. I don't think this would be practical given the space constraints, but maybe you could make it work by sharing the work: move the TV down slightly and move the plunger up slightly. The plunger would stick out above the TV, so you'd have to cover it up somehow.

- Get rid of the plunger and use a Launch Ball button instead. The button doesn't create the same space conflict, so you can put it where the plunger would normally go and still have the TV all the way at the front. If you're not particularly attached to the idea of a plunger, this option has the additional upside that it's a big simplification overall, in that plungers are complicated on a virtual cab by their very nature. A lot of us would never consider doing without a plunger, though, since it's such an iconic pinball element.

- Move the plunger down to clear the TV. This requires moving it down by about 3". Some cab builders take this approach because it lets them both have a plunger and put the TV exactly where they want. I personally don't like the resulting look, though - it gives it a kind of weird home-brew vibe and makes it too obvious that it's not a real pinball machine.

- Move the TV further back to clear the plunger. This has the downside that it creates a gap at the front of the cab before the TV starts, which is unacceptable to some cab builders (who want the TV at the very front). In my opinion, though, a gap at the front isn't a problem, and you can even turn it into a virtue. For one thing, you can fill the space with something resembling the apron on a real machine. I think a 3D element like this adds some nice texture to the otherwise flat expanse of TV screen, and it's an opportunity for some added decorative graphics. For another, you're going to have a front-to-back gap somewhere, because a 16:9 TV simply doesn't have the same proportions as a standard cab. If you put the TV at the very front, the gap all ends up at the very back. I think it creates a more balanced look to split the gap between the front and the back.

Which option is best comes down to the priority ranking you would

assign to these three goals:

- I want a plunger

- I want the launcher at normal height

- I want the TV at the very front

Basically, you get to pick two of these, but you can't have all three.

Pick the two that you think are the most important, and that decides

the question for you:

- I want a plunger, I want it at normal height: then you should move the TV back. Personally, I rank these priorities highest, and this is the solution I like best.

- I want a plunger, and I want the TV at the very front: then you have to lower the plunger to clear the TV. I think that looks weird, but tastes vary.

- I want the launcher at normal height, and I want the TV at the front: then you have to dump the plunger and go with a Launch Ball button. I wouldn't want to forego the plunger, but not everyone feels as strongly.

Inset depth

The first decision you have to make about TV positioning is whether to

install the TV screen flush with the top of the cabinet, or recessed

into the cab by some distance. In the latter case, most cab builders

think of this in terms of placing the TV at the normal playfield depth

of the real machines.

These two main options are illustrated below, for the sake of

clarifying our descriptions, but I wouldn't try to make an aesthetic

judgment from the diagrams alone. The differences in question are

subtle enough that it's hard for an illustration or photo to capture

the full effect.

First, placing the TV flush with the top:

Playfield TV flush with the top of the cabinet, taking

the place of the top glass. The top glass can be added

if you set the TV back by about 1/4" to make room.

And second, recessing the TV into the cabinet to about the depth

of a normal playfield:

TV at roughly the same depth as a normal pinball playfield.

In comparing these for aesthetics, note that we've made the "filler"

areas at the top and bottom more conspicuous than they'd be in a real

build. You'll probably make these a darker color in your actual build

(probably black, maybe with some graphics decorations). We wanted to

make it obvious in the illustrations that they're not part of the TV

screen, which they might appear to be if we made them a flat black.

Pros and cons

Aesthetically, I have a strong preference for the inset version. I've

seen both setups in person, and I find the flush-top version to look

too much like a video game, with the whole top being a TV screen.

Setting the TV screen down into the cabinet makes it look more like a

regular pinball machine, and creates more of a 3D effect. It also

lets you add a raised apron at the front, which adds another 3D

element to contrast with the flatness of the TV screen.

Some people prefer the flush-top version on the theory that the

simulated pinball tables already depict a portion of the inset

depth. I don't find that reasoning convincing, because most of the

pinball programs let you adjust the point of view to show as much or

as little of the side walls on the TV as you want. The less the

better, as far as I'm concerned, because video images of the walls

take away TV space that could be used for actual playfield area, and

they don't look as realistic as real side walls.

In terms of playability, I don't think it makes any difference

one way or the other. For the most part, once you're into a game,

your eye only pays attention to the active playfield, and mostly

ignores the surroundings.

Functionally, each version has its advantages. The inset version

makes room for a flasher panel at the back, which I see as a major

plus, as well as LED strips along the sides. It also leaves

an air gap for cooling between the screen and the top glass (if you're

including top glass).

The flush-top version has the advantage that it rotates the screen

slightly closer to a head-on viewing angle. Everyone knows that the

picture degrades on many flat-screen TVs when viewed from too steep an

angle off to the side, so this might be a concern for some TVs.

However, I think a lot of cab builders get overly worried about this.

Keep in mind that the viewing angle difference between the "inset"

setup and the flush-top setup is only about 2-3°, and they're both

pretty far from head-on. I think on most TVs it will make little or

no difference. If you're concerned about it, test your TV from the

two angles and see if it makes a big enough difference to be the

deciding factor.

A second advantage of the flush-top setup is that it consumes a little

less vertical space in the cabinet. That's usually not a big deal one

way or the other in a full-sized cab, but the extra space might make a

bit difference in a mini-cab.

What is the standard real playfield depth?

If you're using an inset to simulate the playfield depth of the real

machines, what's the authentic distance?

We actually have a fairly large range to choose from, because the real

machines vary quite a bit, mostly by vintage. In the 1970s and

earlier, most machines had very shallow playfield insets: the

playfield surface was typically only about 1½" to 2" below the

top glass, all the way from front to back, and the top of the apron

was almost flush with the glass. In the 1980s, the depth started to

increase to make room for the three-dimensional features that became

common, such as ramps and two-level playfields. A mid-1980s machine

might have an inset of 3" at the front and 6" at the back. Note that

this generation started sloping the playfield relative to the top

glass, so that it had more headroom at the back, to allow for taller

ramps and other features. As the years went on, the 3D features got

even taller. By the 1990s, the playfield depth had increased to

around 4" at the front and 8½" at the back. It reached a

plateau at that point; the latest Stern machines tend to be about the

same.

Recommendations

I much prefer the "inset" style over the flush-top design

aesthetically, so that's my first recommendation. I'd only use a

flush-top design if you have to due to some kind of physical

constraint, like an oversized TV that can only sit on top of the side

walls.

Assuming you're going with the inset style, the depth and angle are

pretty flexible, since the real machines cover such a wide range. I

don't think you need to replicate the precise measurements of any

particular real machine - I think all you need to do to look "right"

is to maintain the general proportions. Specifically, I'd say this

means:

- the playfield should be set in by at least the height of the ball (about an inch)

- it should be angled slightly upward (about 5° to 6° relative to the floor)

- for WPC-style cabinets, the angle should be less than the angle of the top glass, so that the back of the TV is set in deeper than the front

- for older EM-style cabinets, the angle should usually be about the same as the top glass

In terms of looks, that gives us a pretty wide range to work with.

There is one practical consideration that I'd add: if you're using

an apron at the front and/or a flasher panel at the back, you'll need

to leave a little extra vertical space for those. Exactly how much

depends on how you want those features to look. For example, the

flasher panel can be horizontal, tilted, or vertical:

I personally like the tilted style best, but that's probably a matter

of taste more than anything else. In terms of space, a flat

flash panel only needs about 1¼" of headroom, for the height of

the domes. A tilted flasher panel needs more, depending on the angle;

I'd give it at least 2". A vertical panel needs at least an inch (for

the diameter of the domes), but you'd probably want to leave some

margin for visual borders as well.

To summarize my recommendations:

- Use the inset style

- Choose a depth based on the era your cabinet is based on:

- For a WPC-style cabinet, inset the playfield by about 2" from the top of the wall at the front and 4-5" at the back

- For an EM-style cabinet (1970s or earlier), inset by a uniform 1½" to 2", or as much as needed to make room for the flasher panel

Front-to-back positioning

The second decision you have to make about TV positioning is where to

put it front-to-back. Assuming you're building a cabinet to something

like the standard proportions, the playfield area will be longer than

a 16:9 TV, so there will be some leftover space front-to-back. The

extra space typically amounts to about 6" in a standard-body cab.

The question here is whether to split the extra space between the

front and back ends of the cabinet, like this:

...or to put it all at the back, like this:

In either case, some space at the back is actually nice to have, in

that it's a natural place to put a flasher panel (see

Flashers and Strobes) or an LED matrix (Addressable Light Strips).

Space at the front can also be functionally useful, because of the

potential conflict between the TV and the plunger, as described in

"The dreaded plunger space conflict"

above. So you might have already

decided to set the TV back to make room for the plunger.

Even if you're not forced to set the TV back by your plunger setup,

I'd still consider it a valid aesthetic choice. Splitting the extra

space front and back makes for a more balanced look, in my opinion,

and I like the way an apron-like area in the front adds a 3D element.

But many cab builders are very attached to the idea of having the TV

all the way at the front, so that might be a higher priority for you.

For what it's worth, I also thought that way when I was planning my

cab layout, and only reluctantly accepted a front gap after

determining that it was the only workable solution for the plunger

conflict. But as it turned out, I think I'm happier with the

apron-style setup than I would have been with no front gap.

De-case it or not?

When I built my virtual cab, it was common practice to "de-case" your

playfield TV, meaning that you disassembled the TV and discarded the

outer plastic case, keeping only the bare LCD panel and circuit

boards. The point was to remove the bulky exterior bezels around the

perimeter of the screen, which at the time were often quite wide. On

many TVs, the case extended a couple of inches below the bottom of the

viewable screen area to make room for buttons and input jacks. That

was a huge problem for cab builders, because we use the TVs in

"portrait" mode - turned sideways. So if there was a wide area at the

bottom of the TV, it became a wide area along the left or right side

when we turned the TV sideways. Obviously quite undesirable in a cab.

The solution was to get rid of the case. After de-casing, you'd

normally be left with a bare LCD panel. That still had a bezel of a

sort, in the form of a metal frame holding the panel together, but it

was typically fairly thin - maybe 1/2" wide - and the same on each

side.

De-casing is no longer common. There are two big reasons for this.

The first is that it's simply not possible for many newer TVs. Older

LCD TVs were built around self-contained panels, so you could fairly

easily open up the case and extract the panel. The panel was usually

a sealed unit, so it would stay in one piece when you removed it.

With many newer TVs, it seems that the TV is the panel. That

is, there's no longer anything like a separate component inside that

you could call "the panel"; instead, the exterior plastic case serves

as an exoskeleton that holds the parts of the panel together. If you

take off the case, you're left with a bunch of loose parts that won't

stay together on their own. Several people on the forums have

reported discovering this the hard way.

The second reason is that there's no longer as much of a need to

remove the case (even if you could). The whole motivation in the old

days was to get rid of the bulky exterior bezel surrounding the

viewable screen area. Newer TVs generally don't have that bulky

exterior in the first place. The exterior bezels on newer TVs are

usually as minimal as the interior frames were on the old de-cased

panels, thanks to the exoskeleton design. Newer TVs also don't tend

to have any buttons or input jacks anywhere on the front, so there's

no need for one side to be any wider than the others.

I'd only consider de-casing a newer TV if you can find information on

the Web about how to safely de-case the particular model you're

using. In the absence of reliable information on the specific model,

I'd plan on using the TV with its case intact. Take this into

account when shopping by looking for a TV that has minimal bezels.

Use the full case width stated in the spec sheet when figuring which

TVs will fit in your cab. If you're designing a cab around a selected

TV, figure the cab size based on the TV's case width.

Side trim

Unless you're building your cabinet to a custom width to exactly fit

your TV, you'll probably have some space left over side-to-side

between the TV and cabinet walls. Most people want to hide the gaps

as much as possible.

The best option I know of is to use black acrylic strips, custom-cut

to the required width.

You can have acrylic cut to a custom size by a local plastics store or

hardware store. If you're on the west coast, check for a local

TAP Plastics store.

You can also order custom plastic online at

Ponoko.com. They have two

drawbacks compared to a local shop: you'll have to pay for shipping,

and their maximum sheet length is about 31". A TV in the

standard-body size range will usually be about 36" wide. You can deal

with that by splitting the trim along each side into two pieces, but

that leaves a seam.

You attach the trim on top of the TV's side bezels using a strong foam

tape.

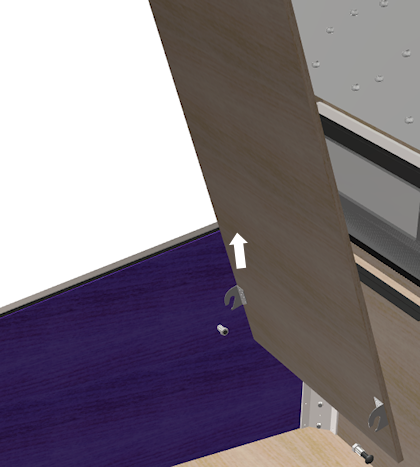

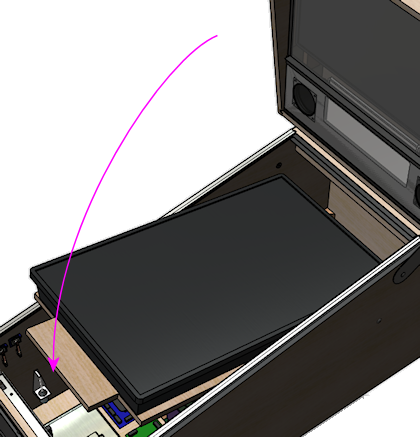

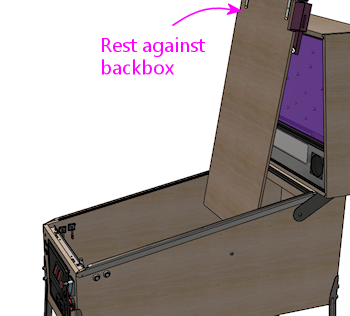

Tilt-up mounting

In a real pinball machine, the playfield is mounted on a hinge at the

back, so that you can tilt it up like the hood of a car.

This gives you easy service access to the interior of the machine.

There's nothing to disassemble, no fasteners to remove; you just take

off the lockbar and lift the playfield.

The reason we're looking at how the real machines do this is that we

can use it as a model for how to mount the TV in a virtual cab.

Access to the interior is just as important for a virtual cab. And we

can copy more than just the idea - we can adapt the mechanisms used in

some of the real machines. As I've said before, it often pays to look

at how the real machines accomplish things, because they came out of

decades of experience solving some of the same problems.

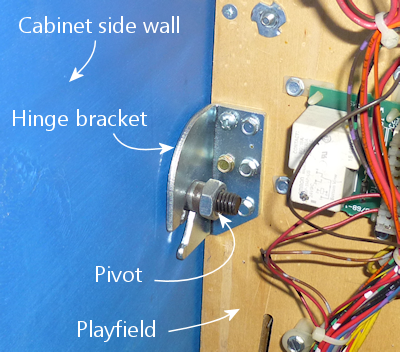

How it works in a real machine

The exact mechanism used on the real machines varies by manufacturer

and vintage. The particular version that I think translates best

to a virtual cab is the one used in Williams machines from the 1980s

and early 1990s. They used a simple but clever scheme, with a hinge

bracket attached to the bottom of the playfield, and a pivot bolt

fastened to the side of the cabinet.

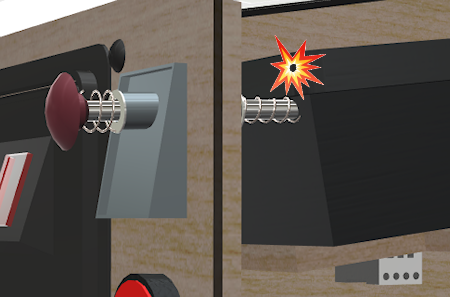

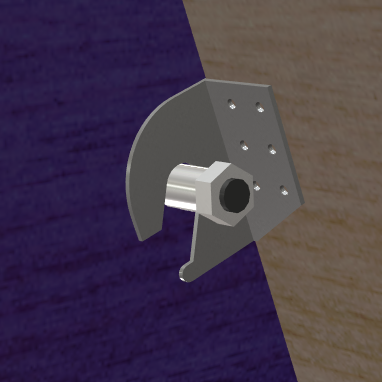

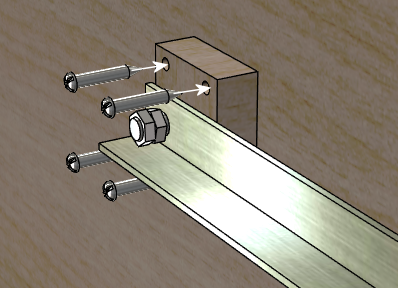

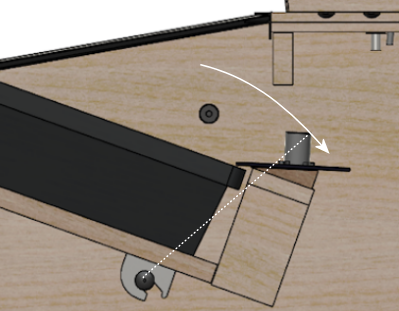

Here's a more schematic view:

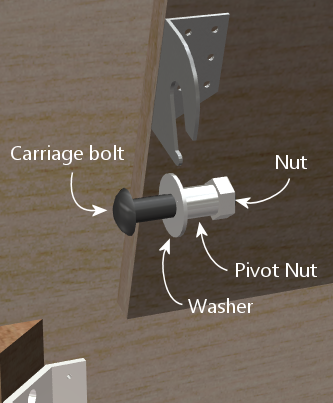

Taking away the side wall of the cab for a moment, here's how this

all fastens to the cab:

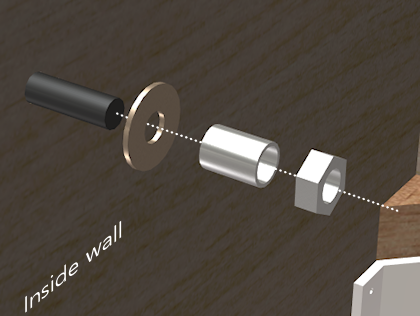

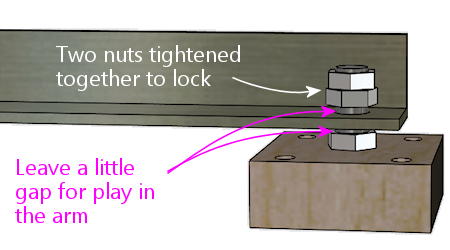

The main fastener is the carriage bolt. (That's a type of bolt with a

smooth round head on the outside, without any screwdriver slots. This

makes it visually inconspicuous on the outside.) On the inside, we

slip a pivot nut over the bolt. The pivot nut is basically a round

metal sleeve that threads onto the bolt; it provides a smooth pivot

point for the bracket. A conventional hex nut is added on the end to

hold lock the assembly in place.

The nice thing about using a carriage bolt as the pivot is that it

only intrudes into the cabinet by about an inch. It doesn't get in

the way of anything inside the cab for maintenance access.

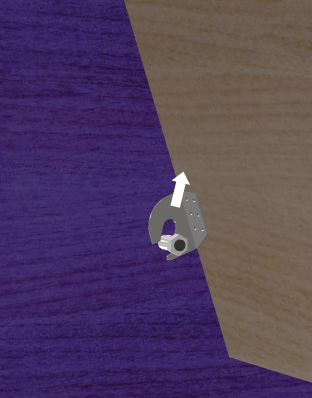

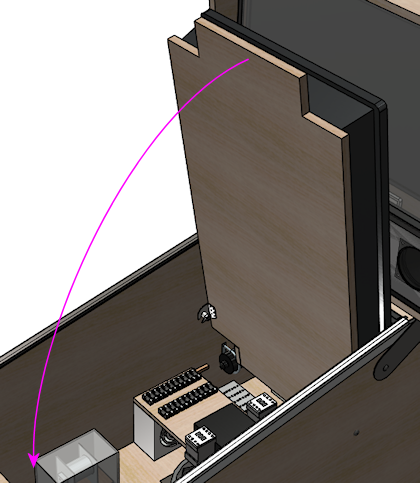

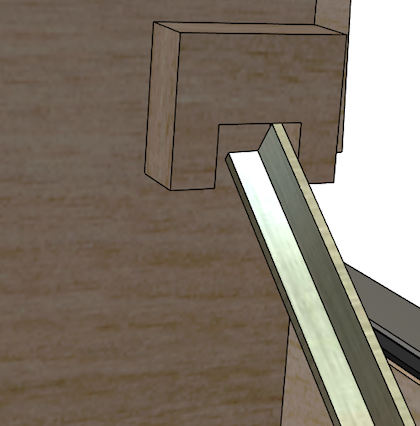

Going back to the bracket, note how it's open at the bottom. The

bracket isn't in any way permanently attached to the pivot pin, like

it would be in a regular door hinge. Instead, the playfield bracket

just sits on top of the pivot. It's held in place by gravity (a

playfield is heavy enough that gravity does a very good job of it!).

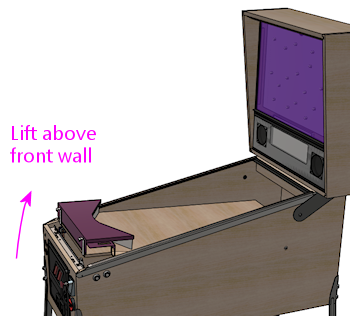

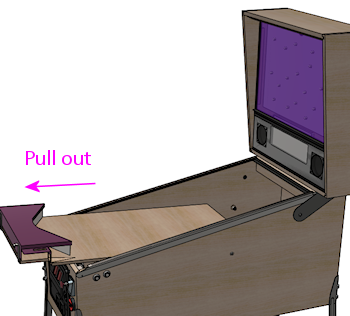

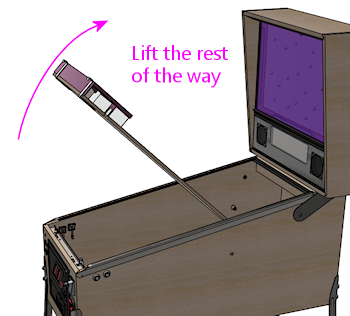

If you want to remove the playfield entirely, it's a simple matter of

tilting it up like this and then lifting it straight out of the cab:

That's the really clever thing about this arrangement. With this

simple mechanism, we get two levels of access, both without any

tools needed:

- For routine access, just tilt up the playfield (or TV in our case) like a car hood

- If you need to remove the playfield (TV) entirely, unplug the power and video cables from the TV and lift it out

There's a surprising third benefit to this design: it's fairly cheap.

Using the real pinball parts, it comes to about $20. It would be hard

to create a similarly functional mounting with generic parts from

a hardware store, and even if you could, it probably wouldn't be

any cheaper.

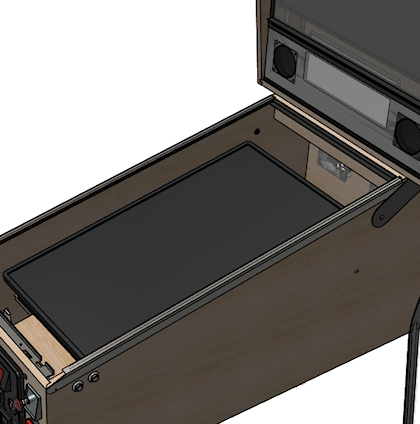

Adapting it to a TV

Here's my all-purpose plan for adapting this to a virtual cab TV. The

general design should work with virtually any TV and with any cab

size, although you'll have to adjust the dimensions if you're not

using the standard WPC cab size.

- Create a plywood base, approximately the size of a standard playfield

- Attach the TV to the plywood base using the VESA mounting holes on the back of the TV

- Attach the pinball playfield brackets to the back of the base, just like they'd attach to a real playfield

- Attach the pivot nuts to the side walls of your cab, just like they'd attach to a real cab

- Drop the TV into the cab so that the brackets rest on the pivots, just like in a real cab

When I say this plan is "all-purpose", I mean not only that it'll fit

different cab sizes, but that it'll work with any of the TV placement

options we've discussed. The diagrams show the setup I like best,

with a recessed TV set about midway front-to-back, with an apron at

the front and flasher panel at the back. But that's all for the sake

of illustration. The plan doesn't force any of those decisions on

you. It's flexible enough to work with many alternative setups:

- You can put the TV anywhere you like front-to-back. The plan uses a platform that holds the TV, running most of the length of the cab. You can place the TV anywhere you like on the platform.

- You can use this plan for a flush-top TV or a recessed TV. It's just a matter of where you position the hinge pivots.

- You don't have to use an apron or flasher panel with the plan. They're optional add-ons.

At each stage in the plan, I'll point out where your TV placement

design decisions come into play.

Parts

The easiest way to implement this design is with the real pinball

parts. The playfield brackets in particular are highly specialized

for this job; there's no generic equivalent. Fortunately, the parts

aren't expensive.

- Playfield holder bracket (left side), Williams/Bally 01-8726-L-1

- Playfield holder bracket (right side), Williams/Bally 01-8726-R-1

- Pivot nut, 7/16", Williams/Bally 02-4244; or 1/2", 02-4329 (quantity 2)

- Carriage bolt, 3/8"-16 x 1-3/4", black, Williams/Bally 4322-01123-28B (quantity 2)

In addition, there are some generic hardware parts, which you can

get from the pinball vendors or from a hardware store:

- Washer, 3/8" x 1" outside diameter (quantity 2)

- Hex nut, 3/8"-16 (quantity 2)

Finally, the mounting base and bolts:

- Good-quality 1/2" to 3/4" hardwood plywood (at least 2' x 4')

- M4 or M6 bolts as needed for your TV's VESA mount, 20mm length for 1/2" plywood, 30mm length for 3/4" plywood (quantity 4)

- Washers to go with the M4/M6 bolts (quantity 4)

The plywood base isn't going to be visible, but you should use

high-quality material anyway, because it needs to be strong and (maybe

more importantly) flat. The cheaper stuff they use for framing and

roofing doesn't tend to be all that flat. You want a nice flat piece

here so that the TV sits securely and doesn't wobble due to a warped

base.

Don't use particle board or MDF. Particle board is terrible at

supporting point weights, as we need to do at the hinges. It also tends

to sag over time.

Strength and weight

The pivot setup puts all of the TV's weight on the hinges when the TV

is raised, so it's reasonable to ask if the hinges are strong enough.

We know that the mechanism has a proven track record on the real

machines, so as long as we're not asking more of it in terms of weight

than the real machines do, we should be safe. I'd estimate that a

pinball playfield (assembled) is in the range of 50 to 75 pounds.

A modern TV in the 40" range is under 20 pounds, and the plywood

should be around 10 pounds. That leaves us with a weight budget of

about 30 additional pounds for other features that we might want to

attach - apron, flasher panel, and solenoid devices to simulate

flippers and bumpers.

So I think we're very safe! The only thing to be concerned about

might be a full slate of unusually heavy feedback devices. Contactors

wouldn't be a problem by any means as they're quite light. Real

pinball mechanisms are heavier, though (they're the main reason the

real playfields are so heavy), so if you're using those you might want

to keep track of how much weight you're adding at each stage. You

can always split things up so that some of the devices are mounted

to the TV platform and others are mounted in the main cabinet.

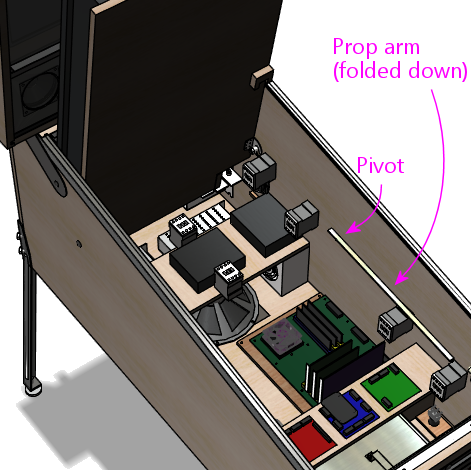

How to install

Here's the step-by-step procedure for building and installing the

universal, all-purpose tilt-up mounting system.

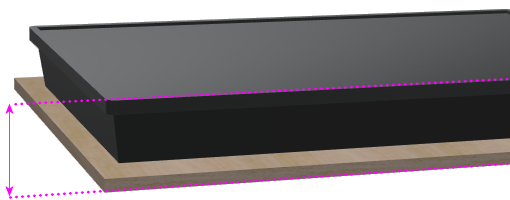

Step 1: Measure your TV's depth. Place the TV on its back on the

plywood sheet you're going to use for the base, making sure it's flush

with the VESA mounting area, like it's going to be when installed.

Measure the height from the bottom of the platform to the top of the

TV.

This measurement will let us figure the alignment position of the

platform in the cabinet that will position the TV's screen surface

where you want it.

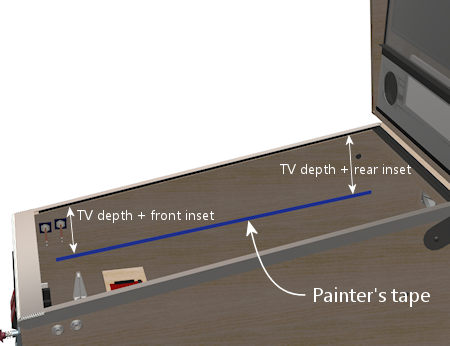

Step 2: Mark where the TV will go. Choose where you want

the TV to go in the cabinet, as described earlier in this chapter.

In particular, figure out the inset depth where you want the

TV screen surface to lie - flush with the top of the cabinet, or

set into the cabinet by some distance.

In your cabinet, measure and mark the positions where the bottom

of the platform will go towards the front and back of the side walls.

The front point should be right around the flipper buttons, and the

rear point should be around the rear shelf.

At each point, calculate the desired TV screen inset depth (the distance

you want between the top of the cabinet and the TV screen) plus the

TV-and-platform depth measured in Step 1.

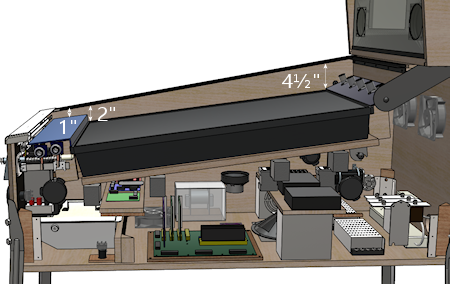

For example, if you like my recommended inset of about 2" at the

front and 4" at the back, and your combined TV-and-platform depth

is 4", you'd mark a spot 6" below the top at the front and 8" below

the top at the back.

Once you mark the front and rear spots, mark a straight line through

the points with pencil or painter's tape. This will be the position

of the bottom of the platform.

Mark both side walls the same way.

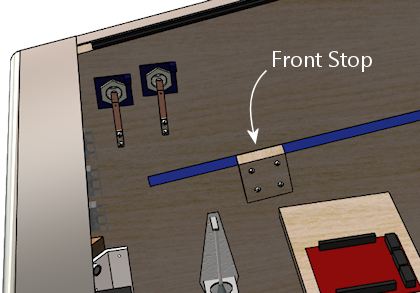

Each stop will have to support about a quarter of the weight

of the whole assembly (the combined weight of the TV, plywood base,

and any feedback toys you attach to the bottom of the base).

You can use a sturdy metal post or a wood block for each stop. It

only has to extend into the cabinet by about 3/4" of an inch to do the

trick, since we're going to make the plywood platform base almost as

wide as the cabinet. I'd suggest using a piece of 3/4" plywood cut to

a convenient size, say 2" x 2", fastened to the cab wall with

four #6 x 1¼" wood screws.

Align the top of each stop with the position where the bottom of

the platform will rest, as marked in the previous step. (If you

used painter's tape to mark the position, you might want to remove

it before installing the block on top of it!)

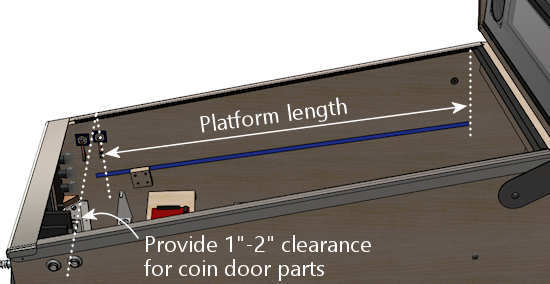

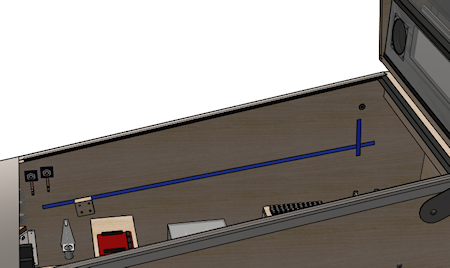

Step 4: Figure the length of the base. The base should

cover the area from about an inch or two behind the coin door

mechanisms, to about directly underneath the backbox shelf.

If you're using the standard-body WPC plans, the result should

be about 40".

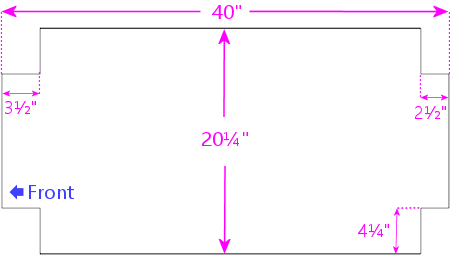

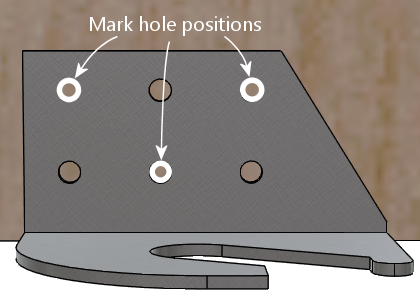

Step 5: Create the plywood base. Cut the plywood base sheet as

shown below, making the following adjustments first:

- Adjust the width to equal 1/4" less than the inside width of your cabinet

- Use the overall length you calculated in the previous step.

TV platform template for a standard-body WPC cabinet. Adjust

the length and width for your cabinet as described above.

The cutouts at the front are there to provide clearance around the

flipper buttons and plunger. They also make it easier to mount an

apron at the front, which we'll come to later. The cutouts at the back

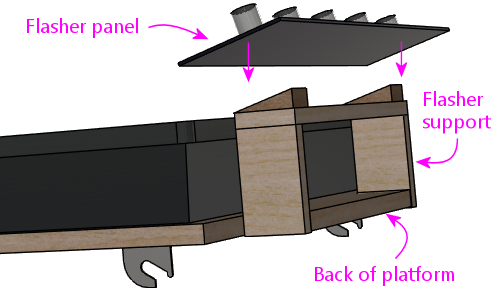

are for mounting a flasher panel.

The shape shown is only a suggestion - it's really just the simplest

shape that fits the requirements. I wanted to provide something that

you can use "off the shelf", but at the same time I don't want to

imply that this shape is the only one that will work. Don't hesitate

to adjust it to fit any special requirements of your own. Just pay

attention to the core requirements that went into this design:

- It needs to fully cover your TV's VESA mounting area

- The front should come as close to the coin door as possible (while clearing the protrusions on the inside), so that you'll be able to reach in through the coin door and lift up the TV when you want to access the cabinet interior

- The area near the back where the hinge brackets are mounted needs to be at full width

- The area near the front where it'll rest on the front stops needs to be at full width

- Front cutouts are required to make room for the flipper buttons and plunger mechanism

- Rear cutouts aren't required, but are helpful for attaching a flasher panel

Step 6: Measure for the hinges. I'm a fan of using the

actual work pieces to make the measurements whenever possible, since

there's less chance of making a mistake reading the ruler, and less

accumulation of rounding errors. So now that we have the platform

ready, we can use it to figure where the hinges go.

This step will also give us a chance to test the fit, to make sure the

platform looks as expected and fits the cabinet properly.

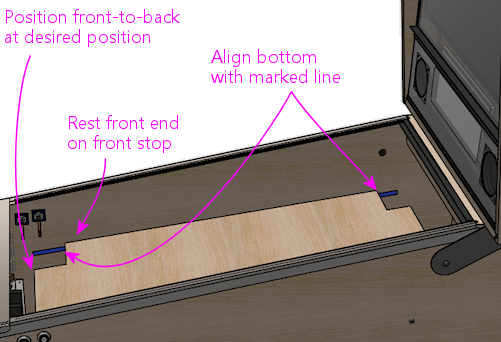

Place the platform in the cab where you want it to be situated when

finished. Rest the front end on the front stops we installed earlier,

and hold up the back end, aligning the bottom of the platform with

the pencil line or painter's tape that marks where it goes.

Judge the position mostly by the front: you want this to be within

easy reach through the coin door, so that you can use it to lift up

the TV when you want to access the interior, while leaving enough

clearance that it won't collide with the coin mechanisms and other

protrusions inside the door. Also check that the back lines up where

expected, right around the front of the backbox shelf. Exact

alignment isn't important.

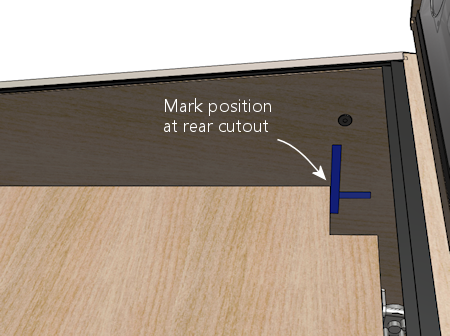

Once it's in the right position, get out your pencil or painter's

tape and make another mark, this time making the position of the

rear cutout.

You can take the platform out, leaving behind the new rear marking.

Now we come to the question of exactly where to position the pivot

point. It should be pretty apparent that the vertical position is

purely determined by the desired TV depth. But the front-to-back

position doesn't have to go at a fixed point. It has to go somewhere

near the back to make the balance work, but beyond that, should

it go at the very back, or somewhere closer to the midpoint? Remember

from the picture earlier of the real pinball playfield that

they positioned it quite a ways from the back. And they

did that for a reason, which will become clear shortly.

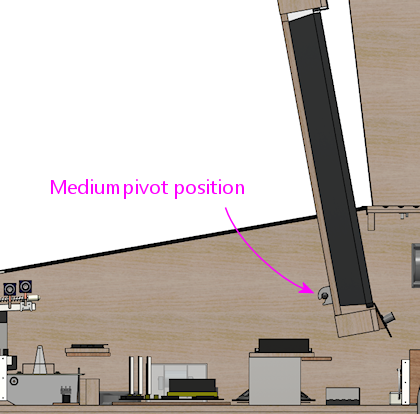

I'm going to give you a one-size-fits-all location for the hinges, but

I also want to let you know how I came up with it, and explain the

trade-offs involved. You might want to check my work and figure out

if you want to adjust the location for your cab.

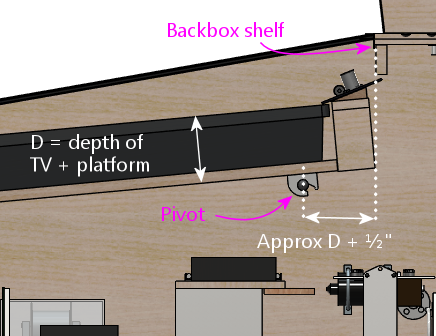

First, the one-size-fits-all location: put the pivot point forward

of the rear shelf by about the combined depth of your TV and platform,

plus 1/2":

This is just a rule of thumb, so it might not be perfect for your

setup. But it should be pretty good for most cabs. The reason this

works is that it's just far enough forward to create clearance with

the backbox shelf to allow the TV to tilt up almost to the vertical.

Now to the details.

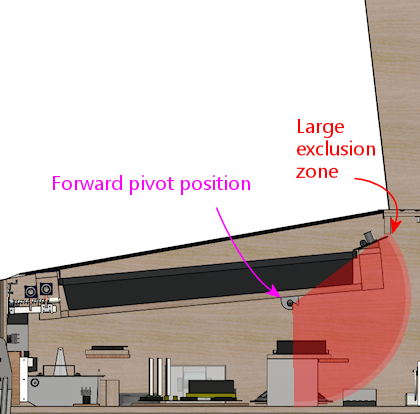

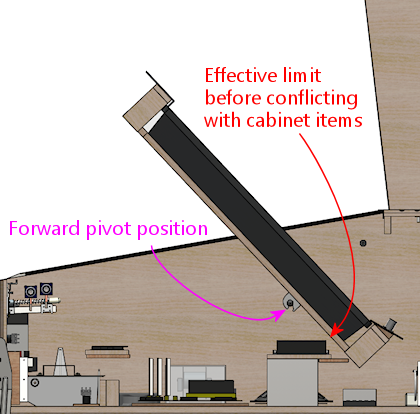

The pivot point is at the nexus of some conflicting geometric

constraints. On the one hand, a pivot point that's further forward in

the cabinet creates more clearance between the playfield and backbox.

On the other hand, the further forward the pivot point, the longer the

overhang at the back that has to dip into the cabinet, which means you

need more empty space within the cabinet to accommodate it.

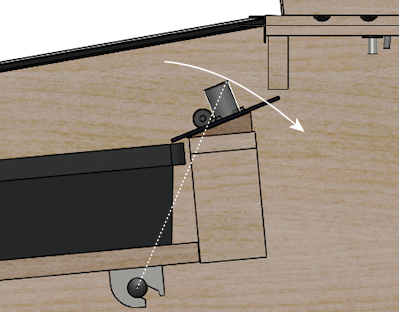

To illustrate, if we put the pivot point too far forward, we get lots

of clearance above, allowing us to lift the TV more than 90°, but

we create space conflicts in the cabinet below:

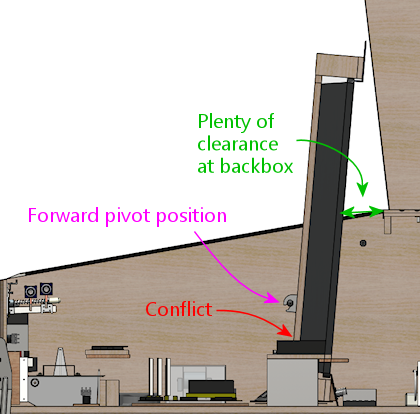

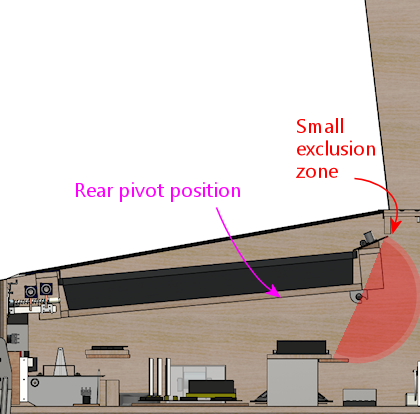

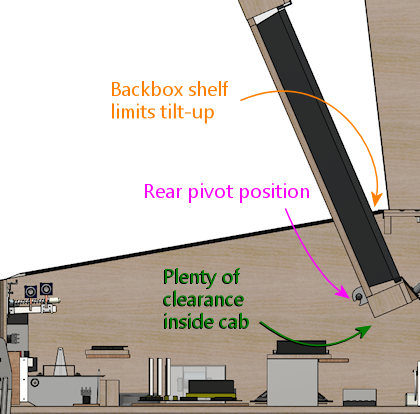

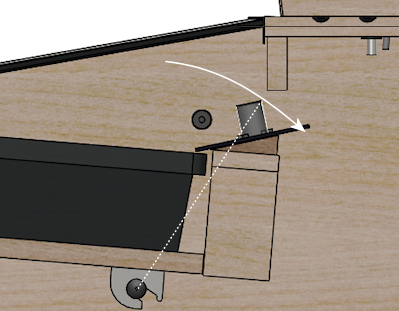

If we put the pivot point too far back, we leave plenty of room in the

cabinet below, but we can't raise the TV very far before it hits the

backbox shelf:

Note how the further-back position allows us to tilt the TV higher

than the further-forward position when we take all of the constraints

into account. But if we look between these two extremes, we can

actually do even better.

There's no solution where we're completely free of the constraints,

but there's a happy medium between the two extremes where we get the

best overall combined clearances, and the greatest overall tilt-up

angle. That's the good news. The bad news is that I can't give you

the magic optimal number for your cabinet. It's probably obvious from

the diagrams that the number will be different for every combination

of TV size, cab geometry, and what's installed inside the cab. The

optimal number for your cab is going to be unique to your cab. So

there are two ways you could approach this:

- Mock up your cab's geometry (with a cardboard model, say, or with a CAD program) and work out the optimal location by experimentation

- Pick a pretty-good-but-not-optimal location based on the rule thumb provided earlier

Even though I'm picky about these things, I think it might be just

fine to go with the pretty-good solution in this case. In my own cab,

I used a less sophisticated hinge mechanism that only lets me tilt up

the TV by about 60°, and while that's sometimes an obstacle, it's

more than adequate for most jobs. I think the pivot system I'm

describing here will do better than that even if you don't optimize

the pivot position perfectly - you should be able to get around

80° without trying too hard to find the perfect position. The

optimal solution will be slightly better, but I think there will be

diminishing returns; if the TV is in the way at 80° tilt, another

another few degrees won't get it out of the way completely. And

remember that this hinge mechanism also makes it easy to remove the TV

entirely, so tilting up the TV isn't the last resort for the rare

cases when you need unobstructed access.

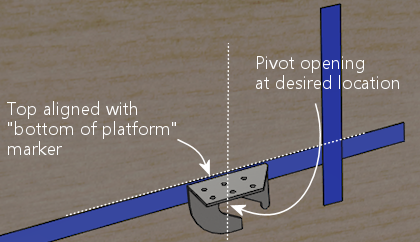

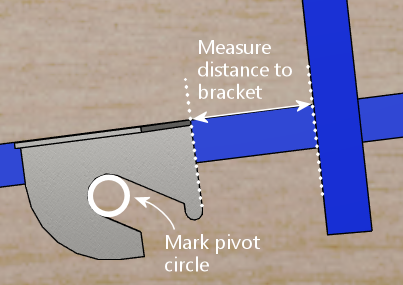

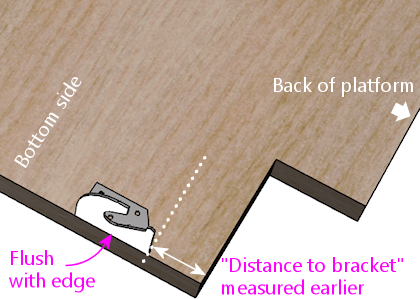

Step 8: Mark the bracket position. Using the distance to

the pivot figured above, hold the bracket against the side of the

cab, with its top aligned with the "bottom of the platform" line

marked earlier, and the pivot opening centered on the pivot distance.

Make two measurements/markings, as illustrated below:

- Measure and record the distance between the "back of platform" and the edge of the bracket. We'll need this number when we install the bracket on the platform later.

- Mark the circle where the pivot goes. We'll need this location to drill the holes for the pivot bolts.

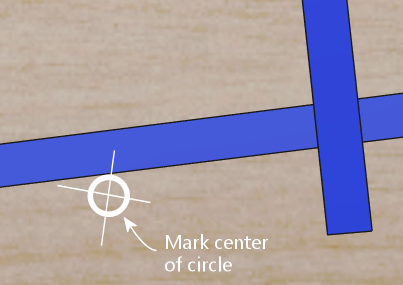

Remove the bracket and mark the center of the pivot circle. This

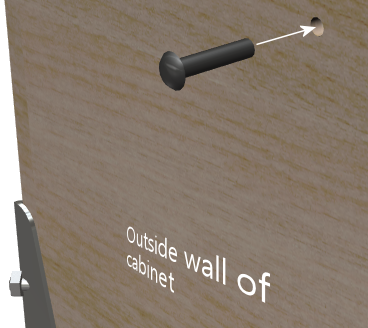

is the drilling location for the pivot carriage bolt.

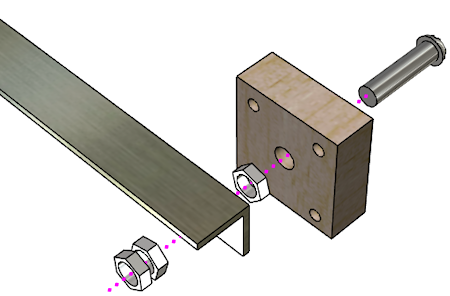

Step 9: Install the pivots. Drill a 7/16" hole in each side

wall at the marked pivot position. Insert a 3/8" x 1-3/4" carriage

bolt into each hole from the outside. Place a 1" diameter washer over

each bolt on the inside, then thread a pivot nut into each bolt and

tighten. Add a hex nut and tighten.

Step 10: Install the platform brackets.

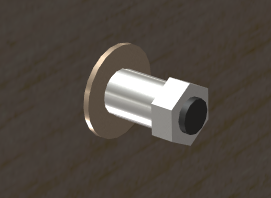

Flip the platform over so that the bottom side is face up. Place

the bracket onto the platform, using the "distance to bracket" that

we measured and recorded in step 8, and aligning the outside edge

of the bracket so that it's flush with the edge of the platform.

Mark the locations of the three holes illustrated below.

Drill holes for #6 machine screws at the marked positions.

Fasten the bracket to the base with #6 machine screws and nuts

in the drilled holes. Use #6 wood screws in the remaining three

holes to further strengthen the attachment.

(In terms of strength, this method of attachment should be at least as

strong as on the real pinball machines I've looked at. They use two

machine screws mated with T-nuts, plus four wood screws.)

Step 11: Figure the TV position. You could figure the TV

mounting position on the platform by measuring and dead-reckoning, but

let me suggest a more direct approach that I think is a little easier.

What we'll do is create a template for the VESA drill holes, and

position the template on the platform using the TV itself itself.

That will let you see exactly what it looks like in place, and

fine-tune the final position.

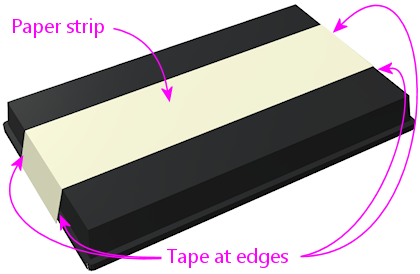

To create the template, put the TV face-down, and stretch a strip of

paper over the back of the TV, covering the VESA mount area. You can

Scotch-tape together a few sheets of 8½-by-11 paper if you

don't have something big enough. Use masking tape at the sides and/or

front to hold the paper in place.

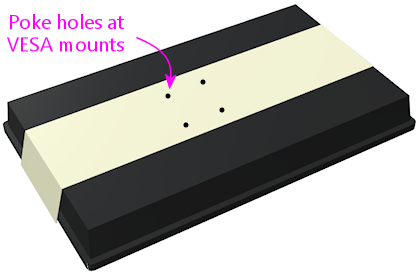

Locate the four VESA mounting holes on the back and poke holes in the

paper at those spots.

Install the platform in the cab, placing it on the hinges and lowering

it to the front stops.

Now flip the TV over, and place it on the platform. Position it where

you want it to go when this is all done.

Once you're happy with the position, untape the template from the TV,

and tape it to the platform instead. Be careful not to let it move at

all while you're transferring it.

Use the holes in the paper to mark the positions of the VESA drill

holes on the platform. Remove the template.

Step 12: Attach the TV. Drill holes for the VESA mounting bolts

at the positions marked in the previous step. Drill 3/16" holes for M4

bolts or 1/4" for M6 bolts. Attach the TV to the base with the

appropriate bolts. Use washers on the outside.

Remember that the typical orientation is with the bottom of the TV

facing the left of the cabinet.

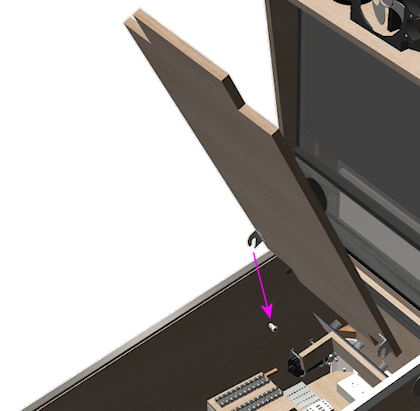

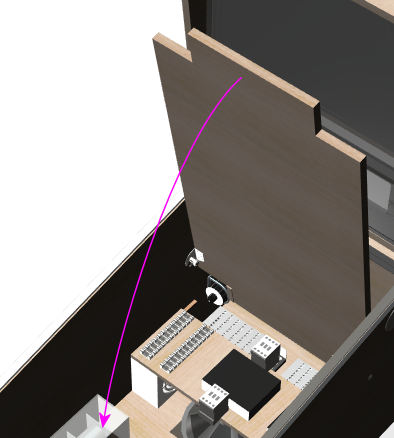

Step 13: Install and test. Hold the TV-and-platform assembly up so that

it's almost vertical. Position it over the pivots in the cabinet.

Lower the brackets onto the pivots. Once they're seated, lower the TV

onto the front stops. Test the tilt action, checking clearances at

the front and back.

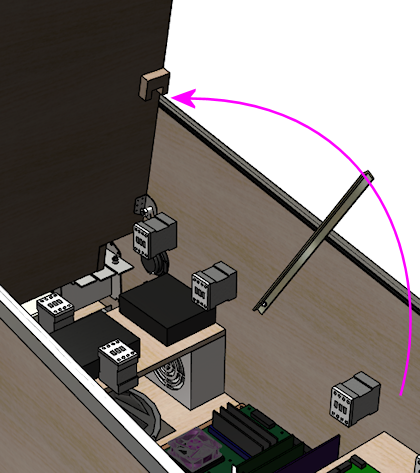

Step 14: Add something to hold the TV up. You'll need something

to hold the TV in the tilted-up position when you want to work inside

the cabinet.

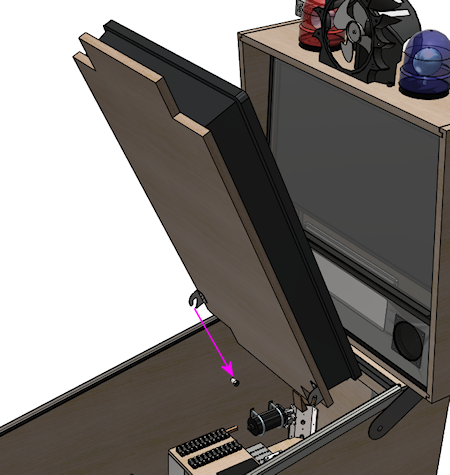

One option is to install a prop rod. The Williams System 11 and WPC

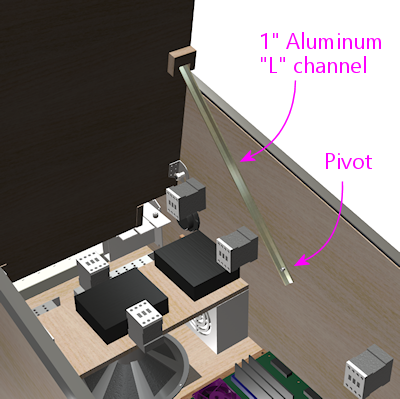

machines use this approach. On my own machine, I improvised one using

1" aluminum "L" channel, cut to a suitable length. It's attached to the

cabinet wall with a large bolt as the pivot.

On the cabinet side, it's probably good enough to use a large wood

screw (perhaps #8) screwed into the cabinet wall as the pivot. This

does have to carry some weight, though, so I wanted something more

robust in my own cab. I used a bolt screwed into a separate wood

plate, with bolts on each side of the plate, and the plate screwed

into the cabinet wall with four wood screws.

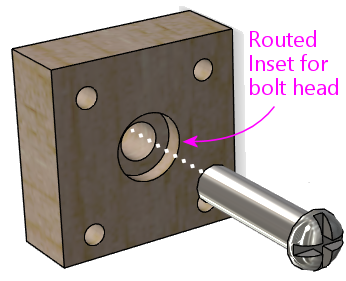

You could do the same thing more simply with a carriage bolt inserted

through the side of the cab wall, if you don't mind another external

bolt head adorning your artwork.

On the playfield side, I made a little wood bracket to keep it locked

in place when deployed:

The prop-arm approach above has worked well on my machine, and it's

not too difficult to set up. If you want a simpler approach, you

could use a lanyard or luggage strap in combination with a couple of

eyelets - one on the playfield, one on the backbox. Simply attach

hook strap to the eyelets to hold the TV up.

Whatever solution you use, make sure it's sturdy enough. It won't

actually have to support a lot of weight most of the time, since most

of the weight will be on the pivots when the TV is tilted up. But you

should make it a little stronger than that, so it won't break or get

dislodged if you accidentally bump the TV while working.

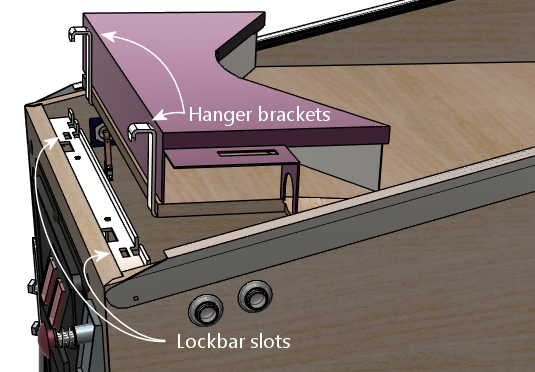

Hanger brackets

There's one more engineering detail on the real machines that I want

to mention.

In the design above, the front end of the playfield rests on a couple

of "stops" on the sides of the cab wall, as described in "Install the

front stops" above.

The real machines do something a little different. They use "hanger

brackets" to support the front of the playfield. These are metal

hooks at the very front of the playfield that fit into slots on the

lockbar:

In terms of the main job of holding up the playfield at the front, our

front stops work just as well. However, the hanger brackets serve

another function that our stops don't accomplish: the brackets also

serve to keep the playfield from tilting up whenever the

lockbar is in place.

Why is that important? Most of the time it's not, since gravity is

enough to hold the playfield down. However, there's one situation

where this changes: if you want to tip the machine up onto its back

for transport. When you do that, the playfield will want to tip away

from the lockbar. On the real machines, the hanger brackets will

prevent it from going anywhere, since the lockbar will hold them in

place. Our front stops won't do that. If you have a glass cover, the

glass will stop it - assuming it's strong enough to support the

weight. I'm not sure I'd want to count on that, especially if I

were putting the thing on a truck.

Given that we're using the standard pinball parts for the hinges, you

might wonder why we didn't also use the standard hanger brackets

instead of the improvised front stops. The problem is the fit. The

hanger brackets are only available in certain sizes that are designed

to fit real playfields. TVs are usually too deep for these to fit

directly. It would be possible to adapt them with some more complex

construction, but I thought the design was already complicated enough

as it is.

I don't have a good alternative solution hold-down solution,

unfortunately. I think the best bet if you want to ship the machine

anywhere would be to simply remove the TV and box it up separately.

It's some consolation that we've made it easy to remove the TV, at

least!

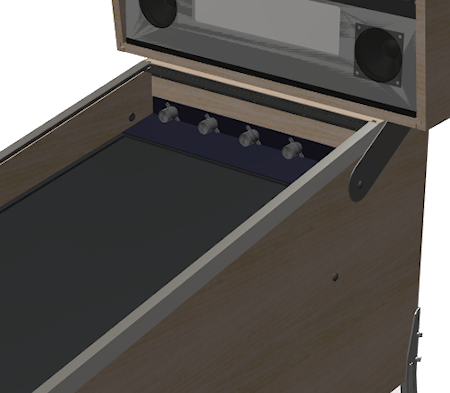

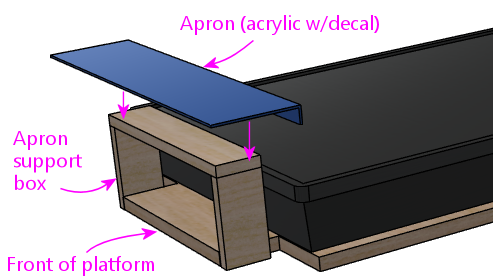

Apron mounting

Once you have the platform assembled, it's fairly easy to add an apron

equivalent, if you have unused space in front of the TV that you need

to fill.

My suggestion is to build a simple box out of thin plywood. The apron

doesn't have to carry any significant amount of weight, so this box

doesn't have to be especially strong. Attach it at the cutouts we

left at the front for the flipper buttons and plunger.

For the visible part of the apron, acrylic works nicely, since it has

such a nice flat, polished surface, and it makes a great base for

attaching a decal with custom graphics. You could also just use a

thin plywood sheet with a nice paint finish. Attach it with whatever

means are convenient, such as glue or foam tape, but I recommend

Velcro to allow easy removal and replacement should you ever want to

make changes.

For ideas about designing the apron's cosmetics, see "Apron" in

Finishing Touches. That section includes a template for

laser-cutting an acrylic cover with cutouts for standard-sized pinball

instruction cards.

On the real machines, the apron sits well above the playfield, usually

2 to 3 inches. You probably don't want quite that much depth on a

virtual cab; this is more about creating an impression than exact

duplication. I think a vertical distance of about 1" or a little less

looks good. On the other end, the apron should be set in a little

from the top glass as well, perhaps another 1" on that side.

Flasher panel mounting

Adding a flasher panel at the back is basically the same as adding

an apron at the front. Build a little box to serve as the platform,

and mount the panel on top of that.

See Flashers and Strobes for more on designing and building the

flasher panel itself, including the electronics and how to

connect it to the software.

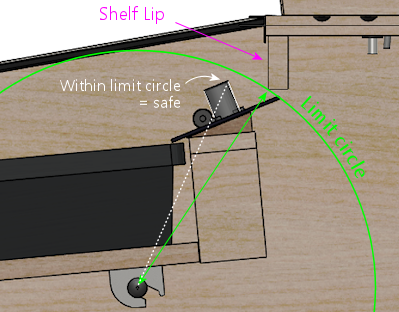

One extra detail that you have to pay attention to with the flasher

panel is clearance with the lip below the backbox shelf. Depending

on how your panel is set up, the domes might stick up above the

bottom of the lip. If they stick up too far, they might hit the

lip when you lift the TV.

The easiest way to be sure is to test it, but you can also figure it

out from the measurements when planning. The key is that everything

rotates around the pivot point, so everything always stays at exactly

the same distance from the pivot point - that is, everything moves

along a circle centered at the pivot. That means that the flasher

domes won't collide with the lip as long as the highest point on each

dome is within the limit circle of the shelf lip:

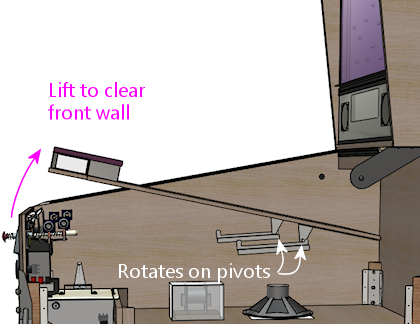

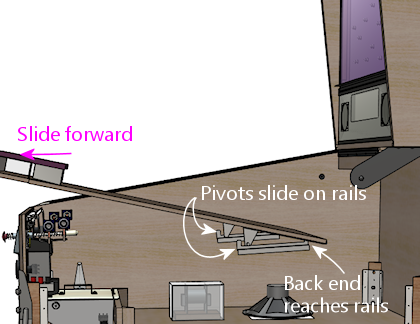

Alternative tilt-up design with a sliding pivot

The later WPC machines and modern Stern machines use a different, more

elaborate design that I at least want to mention, even though I don't

think it translates well to a virtual cab.

The newer machines use a sliding pivot point that lets the

playfield slide forward before tilting up. They switched to

this new system because it provides more vertical clearance than the

old fixed-hinge system, allowing for longer playfields and taller

ramps.

This approach might look attractive for a virtual cab, too, because it

solves some of the geometry problems that we discussed

earlier in "Determine the hinge

position". But on closer inspection, I don't think it actually works

that well for a virtual cab. The problem is that moving the pivot

point forward like this ends up blocking access to a larger portion of

the cab interior. That's fine on a real pinball machine, because the

cab interior is mostly empty anyway - most of the parts you want to

get to for service are on the underside of the playfield. But in a

virtual cab, we tend to install lots of stuff in the cab, so the

slide-and-pivot design works against us in that respect.

Given those geometry drawbacks, as well as the added complexity, I

don't think most virtual cab people will want to implement a design

like this. So I'm only going to offer an overview of how it works,

rather than going into such great detail as I did with the fixed hinge

system. I'd be happy to revisit the subject if there's enough

interest, though, so let me know what you think.

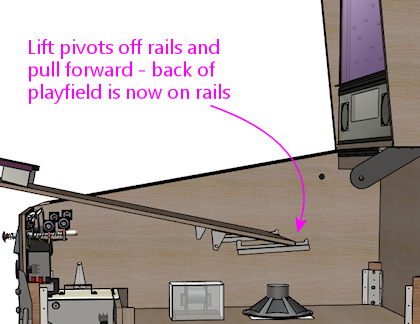

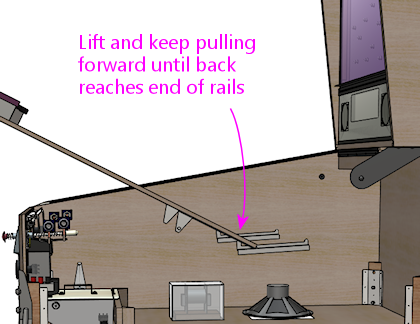

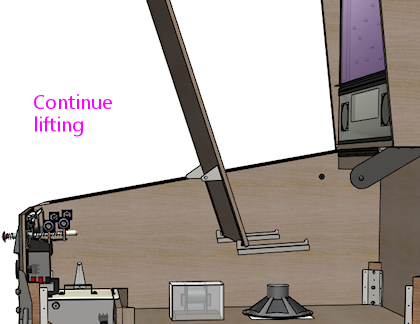

In the Williams WPC machines, they implement the pull-out system with

a rather complicated "slider bracket" mechanism, which uses

spring-loaded levers and latches to provide the sliding capability and

lock the pivot point in place at the forward and aft positions. The

slider brackets are mounted to the bottom of the playfield, taking the

place of the simple pivot brackets of the older design. As in the

older design, the slider brackets rest on top of pivot nuts mounted to

the side of the cabinet. The difference is that the slider brackets

let you move the playfield back and forth across the pivot point, so

that you can pull it out (as illustrated above) before tilting it up.

The slider bracket system works nicely in the real machines, and I

think it would be possible to adapt to a virtual cabinet, but the

parts are expensive - about $75 for a set of the slider brackets. If

you're interested in investigating further, the Williams part numbers

for the slider brackets are are A-17749.1-1 (left side) and

A-17749.1-2 (right side); those mate with the same pivot nuts

(02-4244 or 02-4329) and 3/8"-16 x 1-3/4" carriage bolts as

in the older design.

Stern's modern machines also have a pull-out system, but they use a

completely different mechanism. Stern's system is simpler and

cheaper, but some Stern owners say that it's a bit clunky to operate.

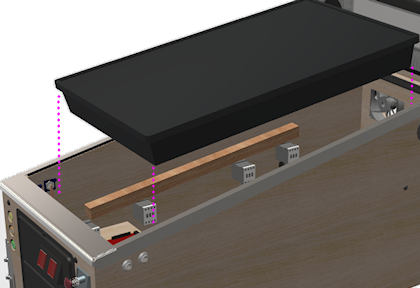

Stern's design essentially inverts the Williams design: it uses pivot

pins on the bottom of the playfield instead of on the side

walls, and has rails mounted on the side walls that the pivot pins

ride on. To slide the playfield forward, you slide it along the rails

until it reaches stops at the front. The clunky part is that the

Stern rails don't have the spring latches that lock things in place at

the different positions in the Williams design; instead, they rely on

gravity and little bumps in the rails. Here's an illustration of how

the mechanism works:

As you can see in the illustrations (which I've tried to keep to

scale), the bottom of the playfield ends up positioned much further

forward in this design than in the fixed-hinge system. That's really

the whole point, since that's how this system deals with the geometry

problems of the fixed-hinge system, but it's a negative for a virtual

cab because it only gives you access to the front half of the cab.

You're likely to have things mounted further back than this.

If you do want to go with this system, I think you could easily adapt

the step-by-step installation procedure outlined earlier for the fixed

hinge system. The parts in the two systems are analogous, so you

should be able to use the same techniques to measure and align

everything. Here are the Stern parts you'd need:

- Pivot brackets, 500-5329-03 (alternates: 500-5329-00, 500-5329-01, 500-5329-02) (quantity 2)

- Left side wall support rails, 535-5990-00

- Right side wall support rail, 535-5989-00

- Carriage bolts, #10-24 x 1-1/4", black (to attach the side support rails to the walls) (quantity 6)

- #10-24 hex nuts (quantity 6)

- #10 lock washers (quantity 6)

- Playfield slides (attach to the rear outside bottom edges of the playfield), 535-5988-01 (quantity 2)

Also see the

EZ slide playfield support brackets at Back Alley Creations.

That's an after-market replacement for the original Stern support

rails that's supposed to offer smoother operation. (The Stern parts

are all metal, without any wheels or bearings, so there's a lot of

metal-on-metal scraping involved. The "EZ slide" replacements use a

smooth plastic for the rails to make it less of a nails-on-chalkboard

experience.)

Rail mounting

A simpler alternative to the tilt-up mounting is to rest the playfield

on rail supports along the sides of the cabinet. This still lets you

access the cabinet interior when needed, by removing the TV, although

it's not as convenient as simply lifting the TV without removing it

as you can do with the tilt-up design.

While this is a little simpler to build than the tilt-up mounting, I

wouldn't use it myself. I consider it too inconvenient, since you'd

have to entirely remove the TV (and unplug all of its cables) every

time you wanted to get into the cabinet. That would turn minor work

into a big hassle.

Some random thoughts if you use this type of design:

- For the supports, I'd only use rails along the sides of the cabinet, not across the width of the cabinet. Cross-bars make it more difficult to reach into the cabinet.

- Be sure your TV is adequately supported underneath. Some TVs might not be strong enough to be suspended from the sides only. You might still want to mount the TV to a plywood base via its VESA anchors, as in the tilt-up mounting design above, then rest the plywood base on the rails rather than placing the TV directly on the rails.

- A base would also allow you to build the flasher panel and/or apron area into the TV assembly, as in the tilt-up design. This lets you remove the whole thing as a unit when you need to access the cabinet interior.

Routed slot mounting

If you want to use a TV that's slightly wider than the interior

width of your cabinet, you can route grooves in the side walls

that the TV fits into.

This is similar to the "rail" design above, in that the TV is

supported from the sides. As with the rail design, you should make sure

that your TV is strong enough to be suspended this way, and if not,

add some kind of base underneath to support it.

The main attraction of this approach is that it can produce a

"wall-to-wall" video screen effect, by hiding the TV's bezels in the

grooves. I can see the appeal, but it has too many functional

tradeoffs for me. In particular, with a routed slot mounting, you'd

only be able to get the TV in and out by sliding it through the front

wall. In other words, you'd have to remove the front wall to

get the TV out, and that's impossible with a conventional cabinet

design, since the front wall is permanently attached. To me, it's a

must that you be able to access the interior of the cabinet at any

time, so I wouldn't use this approach unless I could find a way to

make the TV easily removable without having to disassemble the whole

cabinet.

Permanent installation

Some people install their TVs permanently, fastening them directly to

the cabinet with screws, nails, or glue, with no provision for tilting

up the TV or otherwise moving or removing it. You can't beat the

simplicity of this approach, but I'd personally rule it out for any

cab project of my own, since it would make maintenance and repair so

difficult.