42. Backbox Toppers

Toppers are extra decorations on top of the backbox, such as The

Addams Family's cloud or Whirlwind's fan. A few titles

over the years included toppers as original equipment, but not all

that many, so they were a great novelty feature that helped a machine

stand out from the crowd in an arcade. In more recent times, pinball

collectors have become fond of adding after-market toppers to every

machine in their collections that didn't already have one from the

factory.

Virtual cab builders like their toppers as well, but often for

different reasons. For the real pinball machines, toppers are mostly

about novelty and decoration. In the virtual world, in contrast,

toppers tend to be more about function than decoration. There are

certain feedback devices that just won't fit anywhere else,

particularly fans and beacons. We virtual cab builders tend to view

the topper area primarily as free space for feedback toys.

I think it's worthwhile in a virtual cab to take both views of the

topper - it's a functional feature, but it's also part of the artwork.

We all put a lot of effort into our cabs and want them to look as

great as they play, so it's worth thinking about how to incorporate

the topper elements into our visual themes. It's nice for the topper

to feel like a natural extension of the cabinet art, rather than just

a bunch of gadgets bolted on top.

Let's start with a look at how some of the real machines used toppers

to enhance their visual theming, to get some ideas about how we can

do the same thing.

What makes a good topper?

The obvious place to start looking for ideas for a virtual cab topper

is in the real machines. If you do a Web search for "pinball topper",

you'll find all sorts of after-market toppers for sale. Most of these

are add-ons for machines that didn't have factory toppers, though, and

for the most part they're not all that imaginative (in my opinion, at

least). A lot of them are just acrylic signs that copy some of the

cabinet artwork, and most of the rest are some little doo-dad that's

vaguely related to the theme.

The best toppers on the real machines, for the most part, are the ones

that came as factory equipment. Many of those were thoughtfully

integrated into the theme and formed a part of the overall artwork.

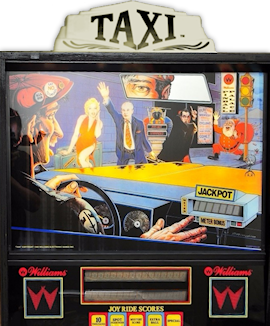

One of my favorite examples is the taxi cab roof sign from Taxi

(Williams, 1988). It's the perfect icon for the game's theme, but it

also meshes with the backglass art, sitting right on top of the taxi

depicted in the art. It's a clever extension of the backglass

painting into the 3D space above the backbox.

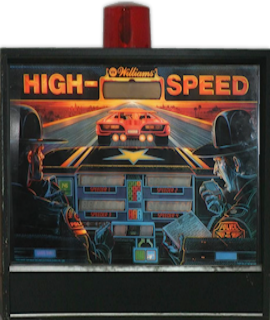

Along the same lines, a number of police-themed pinballs over the

years featured rotating beacons, or even complete police-car light bars,

as toppers. Police themes are nearly as common in pinball as in

CBS dramas, so there are lots of examples, but the canonical

one is High Speed (Williams, 1986), where the beacon fits

into the backglass art using exactly the same trick as Taxi's

roof sign:

A beacon isn't just a passive decoration, either. It can be an active

part of the game action, lighting up and spinning in sync with events

in the game. It's no wonder they used these over and over on the real

machines. They even used them in a few cases where it's hard to see

any relation to the theme. One curious example is

F-14 Tomcat (Williams, 1987), which had not one, not two, but

three beacons.

I wouldn't consider this one to be good integration of topper and

theme. Even so, it's understandable why Williams used beacons so

often, since they add not just an extra decoration, but also a

functional element, in the form of a light show.

Another great functional topper is the fire bell on Fire!

(Williams, 1987). It's the sort of bell you'd expect to see on an

antique fire wagon, so it's a good theme icon, even if it doesn't meld

as seamlessly with the artwork as the Taxi sign and High

Speed beacon. Like the police beacons, it's an active part of the

game's sensory effects - it has a solenoid hammer that rings the bell

when certain events occur in the game.

Yet another brilliant functional topper is the cloud-shrouded fan on

Whilrlwind (Williams, 1990). It's the perfect active toy for

the theme; the fan activates during multiball modes and other events

in the game, creating a tactile sensory effect from the blowing air.

The cloud shape of the enclosure meshes with the backglass artwork,

extending the stormy sky in the art into the space above the

backbox.

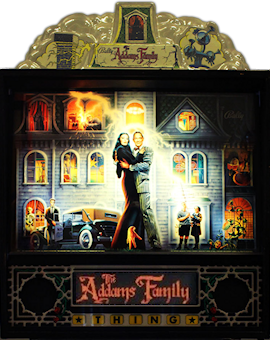

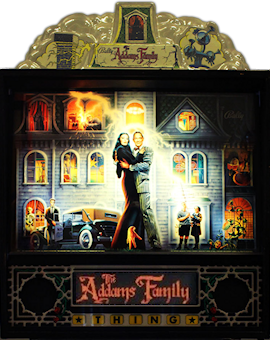

The somewhat similar cloud topper on The Addams Family (Midway,

1992) takes the same approach, and also serves as the top of the

Addams mansion, whose roof extends out of the frame at the top of the

backglass. It doesn't have anything as dramatic as the

Whirlwind fan, but it has flashers inside that simulate a

lightning storm when you start a multiball mode.

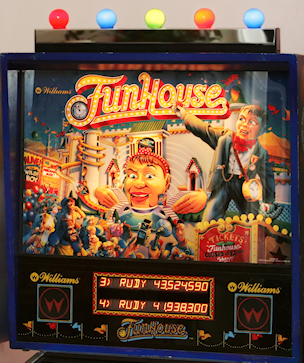

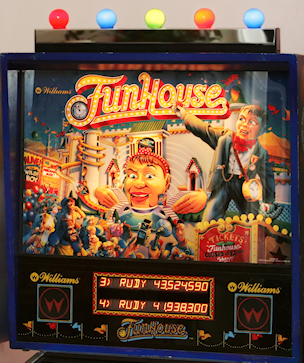

Funhouse (Williams, 1990) didn't have a topper as original

equipment, but here's an example where someone came up with an add-on

topper that's as good as anything that came out of the factory.

Heinz-Peter Bader.

designed this topper for his own

Funhouse. He took a vanity

mirror light - the kind with a row of big round bulbs, like in the

stereotypical actor's dressing room mirror lights - and filled it out with party

bulbs in assorted colors, then put it on top of the machine with the

bulbs pointing up. (I've seen at least one other similar

Funhouse

topper mentioned in a pinball forum, so I'm not sure who came up

with the idea first, but this is certainly a nice implementation

in any case.)

Photo courtesy of Heinz-Peter Bader

It's interesting to compare this design to the various after-market

commercial toppers for Funhouse that the "mods" companies sell.

The bulb topper works so well because it's perfectly in scale and it

captures the carnival atmosphere of the theme, plus it's a natural

extension of the backglass artwork (which is already festooned with

little marquee bulbs) into the space above. In contrast, all of the

commercial topper I've seen for Funhouse just reiterate

something from the artwork, without feeling like part of it: a giant

"Admit One" ticket, a cut-out of Rudy. They do nothing to merge with

the backglass art.

Virtual cab toppers

Virtual cab builders usually take a utilitarian view of the topper,

focusing on the functional elements. There's a fairly standard set of

feedback devices that most cab builders incorporate in their toppers:

Most cabs have at least one of these, and many use all of them.

They're all great additions functionally. Beacons, flashers, and

strobes all make nice light shows, and a fan adds a wonderful tactile

element that movie theaters would market as a "4D experience" with

a $10 ticket surcharge.

But does a big pile of devices make for a "theme"? Well, from one

perspective, it actually does. One way to see a virtual cab is as a

whole arcade's worth of pinball tables in one box. So you could say

that the theme is "all the pinballs" - which makes "all the topper

toys" an apt fit.

Personally, though, I like the idea of giving a virtual cab some kind

of theme more personalized than "all the pinballs". I discuss that

idea a bit in

Cabinet Art. If you

are giving your

machine a specific theme, I think it's also a nice touch if you can

extend your theme to the toppers.

Of course, functionality is still the starting point in choosing which

devices to include. I'd never suggest that you should forego a fan

just because your theme doesn't have an obvious connection to air

circulation. But maybe you can find ways to work some of the

functional elements into your theme, even though the theme isn't the

reason you included them. For example, on my cab, I came up with a

custom plastic enclosure for the fan that's meant to look like a

star-burst, to go along with the outer space theme of my cab graphics.

So I didn't really try to make the functionality of the fan fit the

theme, but I did at least try to work its shape into the visual

layout. (If you're interested in my specific topper design, you can

find some more details

below.

Some ideas for how to work your toppers into a theme:

- Brainstorm for natural real-world "topper" items fitting your theme,

like Taxi's sign topper.

- Think about custom enclosures for one or more of the items. The fan

is perhaps the most obvious enclosure to customize (like I did on my

cab), since you need some sort of enclosure anyway, and it's easy to

build around a bare motor-and-blade fan core. You could also create

your own custom covers for beacons or strobes, or work them into a

larger enclosure like a police-car light bar.

- Consider versions of the topper devices or exterior finishes that

fit your theme. For example, if you're using a steam-punk theme, give

your toppers a Victorian industrial look, with brass finishes and

exposed rivets.

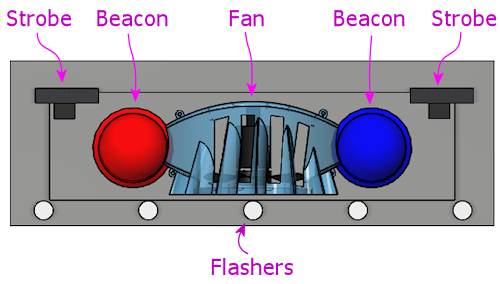

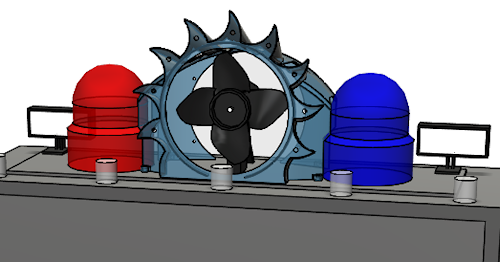

The Pinscape topper

The topper design that I came up with for my own pin cab is very

specific to my theming, so I doubt it'll be of much interest to most

pin cab builders other than as one more example. But in case anyone

wants to reproduce it or use it as a starting point, here are some

details about the design.

Most of the topper is made from off-the-shelf parts:

- A row of five standard pinball flasher domes with high-power RGB

LEDs inside is arrayed across the front edge. These are simply wired

in parallel with the main flasher board at the back of the playfield,

so they always light up at the same time and in the same colors as

the main flashers. See Flashers and Strobes for details on setting

up a standard flasher panel.

- A pair of Peterson 771 dome-shaped rotating beacons, one in red and

one in blue. See Beacons.

- A pair of "22 LED white strobes" that you can find on eBay.

See Flashers and Strobes.

The centerpiece is a custom-built fan with a 3D-printed plastic

enclosure.

The fan is built with a generic 12V DC motor with a 1/4" shaft, mated

to a press-on plastic blade. The blade is a part originally used in

microwave ovens, Thorgren model number 6C2504C1, in black. This

happens to be the same OEM part that Williams used for the topper fan

in Whirlwind, so I was delighted to be able to find the exact

same part. But don't worry if you can't find that particular blade;

eBay has lots of similar fan blades that look just about the same.

Just look for a 6" fan blade with a shaft bore that's the same size

as your motor's shaft. A good search term to try is 6" fan

blade.

To mount the fan motor, I rigged a simple bracket using sheet metal. I

don't have any tricks to suggest here; the bracket I came up with

isn't particularly clever or elegant. You just need something that

you can attach to the motor body to hold it at the right height above

the backbox roof.

For more on building a fan like this from parts, and for details

on how to wire a fan to your output controller, see

Fans.

The fan enclosure is designed to fit between the beacon domes, to

create the impression that the enclosure and domes are connected. The

area around the fan opening is meant to suggest a blazing sun, in a

sort of cartoonish style.

You can download 3D plans for my fan enclosure in STL format here:

Note that the ZIP file contains "front half" and "back half" models in

addition to the full model. I created the half models to fit the

limits of the specific manufacturing process I used, so these probably

won't be useful unless you happen to use a printer with very similar

constraints, but I included them just in case.

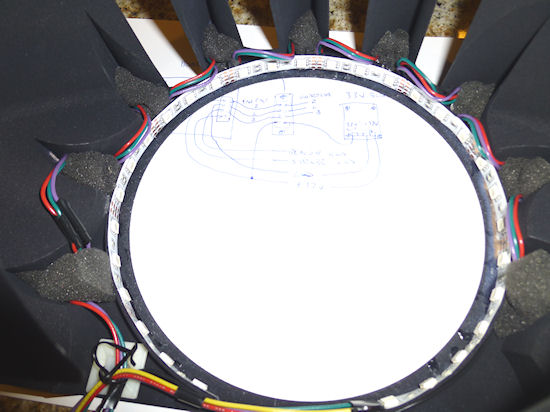

There's one more detail worth mentioning: the fan enclosure is decked

out with lighting. (If you want to see it in action, I made a short

video:

www.youtube.com/watch?v=wJ1czPnjvDQ.)

The fan enclosure has two types of lighting. The first is one of

those common 5050 RGB LED strips, installed around the perimeter of

the front fan opening. This is the same type of LED strip normally

used for

under-cab lighting. If you look

carefully at the fan enclosure model, you'll see a little lip on the

inside of the opening, about 1 centimeter deep. That's the mounting

surface for the LED strip. The strip is mounted on the inside of this

lip, so that the LEDs face inwards towards the center of the opening.

This creates a nice ambient light effect inside the fan. I wired the

LED strip straight to my undercab lighting, so it shows the same

colors as the undercab lights. That creates a nice effect with the

output in DOF set to show the "undercab complex" effects, which

changes the LED strip colors in response to game events. It makes the

fan interior lighting fairly dynamic.

The second bit of lighting installed in the fan consists of nine

high-power RGB LEDs, arranged around the perimeter of the opening,

facing forward. Again, looking carefully at the STL model, you'll see

a small circular hole in each of the "points" of the star-burst shape.

These holes are the right size for typical 3W RGB LEDs, of the same

type commonly used for RGB flashers, but in this case, without

the aluminum "star" base that's usually used for the flashers. You

can find these LEDs on eBay by searching for "3W RGB LED" - they look

like this:

These are actually the same LEDs used in the "star base" type. The

only difference is that they're sold as bare LEDs, not mounted to the

aluminum heat sink base. The procedure for wiring them is the same as

for wiring the flasher LEDs; see

Flashers and Strobes for more on

that.

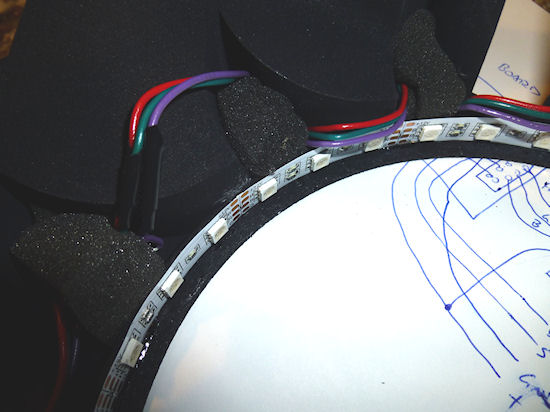

The method I used to mount the LEDs in the fan enclosure is inelegant

and a little tricky (it takes some manual dexterity and a bit of

patience), but it worked well and has held up well over the several

years since I built it. I started by soldering hookup wire to the

LEDs, with just enough wire between adjacent LEDs to reach from one

hole to the next. The LEDs are wired in series, meaning that

the "+" side of one LED connects to the "-" side of the next LED, and

so on down the chain. There are no resistors in this chain - just the

wires and the LEDs. Once all of the wiring was soldered, I arranged

all of the LEDs into the desired locations, poking out through the

star-burst holes. This is the part that requires dexterity and

patience.

And now for the part that's truly inelegant. To secure the LEDs in

place, I stuffed some packing foam into the pockets behind the LEDs.

I tried some other approaches, the best hope being 3M VHB tape (which

is pretty amazing for many similar applications), but that didn't

work; it's hard to get anything adhesive to stick to 3D-printed

plastic, since the surface tends to be uneven and powdery. The

packing foam turned out to work surprisingly well, and it has the nice

feature that it's easy to remove if any of the LEDs ever needs to be

replaced or if a solder joint ever breaks.

Controlling the 3W perimeter LEDs is almost a whole separate project.

There are two main parts:

- The first is the power supply for the 3W LEDs. Wiring LEDs in

series means that you need to supply them with a voltage that's higher

than the sum of the VF ("forward voltage") values for all

of the LEDs. For 9 of the 3W RGB LEDs, this works out to about 33V.

So I used a DC-to-DC step-up buck converter to convert power from a

12V supply to 33V. (You can find such step-up converters on eBay;

they run about $10 for the size needed here.)

- The second part is something to control the LEDs. You could just

wire them to your DOF output controller, and assign them to one of the

existing DOF device types, such as the strobes or under-cab lights. I

wanted something a little unusual, though, which required some more

custom electronics. What I wanted was to coordinate the LEDs with

both the strobes and the beacons: when the strobes fire, I want the

LEDs to flash white, and when the beacons run, I want the LEDs to

flash rapid red and blue patterns like a modern police cruiser. You

might be able to produce something like this with DOF directly,

but it seemed easier in this case to build a little microcontroller

project instead. As usual with microcontrollers, GPIO pins provide

the connections to the outside world: GPIO input pins connect to

the DOF outputs for the strobes and beacons, so that the controller

can monitor DOF activations on those devices, and GPIO output

pins connect to the fan LEDs, via MOSFETs. I wrote a small custom

program for the microcontroller that watches the input connections

from DOF, and when it sees one of them activate, it generates the

appropriate light show on the fan LEDs.

The ZIP file linked above (with the 3D design for the fan

enclosure) contains a hand-drawn schematic for my controller

circuitry, and the C++ control program for the Trinket. The

program is designed to be compiled and downloaded into the

Trinket with the Arduino IDE. I apologize for the rough

appearance of the schematic; this is directly from my original

working notes, and I haven't had a chance to clean it up

into a proper presentation.

Reviewing this circuit plan with fresh eyes, I see a couple

of changes I'd suggest, if you plan to deploy this in your own cab:

- Add a diode (1N4007 should work

nicely) in series between each optocoupler cathode

(pin 2 of the PC817) and the DOF output controller port,

with the striped end of the diode on the DOF port side.

This will avoid any danger of feeding back the beacon/strobe

supply voltage into the optocoupler LED. (LEDs don't typically

have very high reverse voltage tolerance on their own.)

- You might need to add a capacitor, connected

across the Trinket power supply pins, to filter

electrical noise from the rest of the system. You'll

know this is necessary if the Trinket randomly resets

or behaves erratically; if it's stable, don't worry

about this. If you see any glitchy behavior, try

adding a 0.1uF capacitor with its leads connected

to the Trinket's BAT and GND terminals. Position

it as close to the Trinket as practical.

If erratic behavior persists, try different size

capacitors, even up to large sizes like 1000uF.

Sometimes two capacitors in parallel work even

better than one, such as a 0.1uF and a 100uF.

(Larger capacitors, 100uF and above, are

usually electrolytic, which have a "+" and "-"

side, so be sure to connect the marked "-" lead

to the GND terminal. Smaller "disk" capacitors

aren't polarized. See Capacitors for

more if you're not sure.)

Note that my circuit design doesn't use conventional

current-limiting resistors for the LEDs. Instead, it uses

a feedback loop on the MOSFETs to throttle the current through

the LEDs. I did it this way mostly because I was curious

about how to create a current-limiter circuit like that.

I don't think it's all that much better than the simpler

approach with ordinary resistors, since ultimately it's just

using the MOSFETs as variable resistors and burning off

the extra power as heat, just as fixed resistors

would. But it seems to work nicely, and it does have the

slight advantage that you don't have to figure out the right

resistor size for each channel; the feedback circuit

amounts to a little analog computer that does the math

for you each time you apply power.